My dog-eared but much loved copy of Lanark:

I first encountered this marvellous, undefinable book around thirty years ago, while living in Scotland. It's a wonder - part fantasy, part realist novel, part metatextual experiment - an entity like no other book I'd ever read. Told in four parts, it begins with Book Three.

I wish I could put my hands on my hardcover of Poor Things, because then I could show off the gorgeous design worked into the inner covers. My immediate thought was: if they can do this, why aren't all books this beautiful?

Thank you for the words and pictures, Mr Gray. And may we all work as if we lived in the early days of better nations.

Tuesday 31 December 2019

Friday 20 December 2019

Wednesday 18 December 2019

Looking for an Estonian translator

Recently I took part in a very enjoyable long-form interview with Reidar Andreson, on behalf of the well-established Estonian SF magazine Reaktor. In the course of our communication, Reidar mentioned that my short story "Pandora's Box" had been translated into Estonian in 2011, and wondered if the story had gone on to be translated into any other languages.

The background here is that in 2009 I wrote a short story, the aforementioned "Pandora's Box", which was then translated into Finnish in time for that year's Finncon in Helsinki. As part of a stunt, cooked up with the excellent Toni Jerrman, we had arranged for the last English copy of the story to be destroyed on stage at the convention, and this duly happened:

To be clear, no other English version of the story existed. Once we had that final print out, and Toni had completed the translation, I destroyed all my own versions of the text. In the ten years that followed, I have never stumbled on a forgotten backup or intermediate draft. In fact, I only have sketchy memories of the story itself. It's about 8000 words, I think, is set primarily on Titan, and deals in some fashion with Many Worlds and the Fermi paradox.

My intention had been that the world would be so galvanised by this experiment that the story would quickly rush from Finnish to other languages, inevitably (and hopefully) changing a little each time, until it eventually found its way back to English. Astonishingly, this never happened! The story got as far as Estonian, and stopped there.

What I would like to do, in a humble way, is continue the experiment, but to do that I'll need a willing party to take the Estonian text (which I may not have, but Reidar may be able to assist with) and then translate and publish it into some non-English language. Reidar is making enquiries, but I thought it wouldn't hurt the put the word out here, and see if there are any takers. The ground rules are straightforward: any interested party (website, magazine, etc) may have the story for free on a non-exclusive basis, but it must be translated with reference to the Estonian version alone, not the Finnish one. I, in turn, will offer assistance with reasonable translation costs, subject to correspondence.

I would think it would make a far more interesting journey if the story were not to come back to me too quickly, so - as an additional constraint - I'd prefer it if the story were translated into a language that isn't too adjacent to English, however we may define that. Estonian to Russian would be great, for instance - or even Estonian to Japanese. But not Estonian to French: too easy for it to make the final step.

A long shot, I admit, but perhaps worth a try.

Al

The background here is that in 2009 I wrote a short story, the aforementioned "Pandora's Box", which was then translated into Finnish in time for that year's Finncon in Helsinki. As part of a stunt, cooked up with the excellent Toni Jerrman, we had arranged for the last English copy of the story to be destroyed on stage at the convention, and this duly happened:

To be clear, no other English version of the story existed. Once we had that final print out, and Toni had completed the translation, I destroyed all my own versions of the text. In the ten years that followed, I have never stumbled on a forgotten backup or intermediate draft. In fact, I only have sketchy memories of the story itself. It's about 8000 words, I think, is set primarily on Titan, and deals in some fashion with Many Worlds and the Fermi paradox.

My intention had been that the world would be so galvanised by this experiment that the story would quickly rush from Finnish to other languages, inevitably (and hopefully) changing a little each time, until it eventually found its way back to English. Astonishingly, this never happened! The story got as far as Estonian, and stopped there.

What I would like to do, in a humble way, is continue the experiment, but to do that I'll need a willing party to take the Estonian text (which I may not have, but Reidar may be able to assist with) and then translate and publish it into some non-English language. Reidar is making enquiries, but I thought it wouldn't hurt the put the word out here, and see if there are any takers. The ground rules are straightforward: any interested party (website, magazine, etc) may have the story for free on a non-exclusive basis, but it must be translated with reference to the Estonian version alone, not the Finnish one. I, in turn, will offer assistance with reasonable translation costs, subject to correspondence.

I would think it would make a far more interesting journey if the story were not to come back to me too quickly, so - as an additional constraint - I'd prefer it if the story were translated into a language that isn't too adjacent to English, however we may define that. Estonian to Russian would be great, for instance - or even Estonian to Japanese. But not Estonian to French: too easy for it to make the final step.

A long shot, I admit, but perhaps worth a try.

Al

Monday 16 December 2019

Tales of Known Space

Early on in my writing career, and inspired by the likes of Larry Niven and others, I began to make up invented planets and locations around actual stars in our neighborhood of the galaxy. Since my stories were based around the idea of slower-than-light travel, I did what everyone else did at the time: looked up a list of moderately nearby stars and cherry-picked the ones I wanted for my fictional universe. It's for this reason that Chasm City is on a planet orbiting Epsilon Eridani, which is a bit smaller and cooler (and younger) than our own star, but still suitable enough for science fictional purposes.

It's quite a fun game, and one can easily spend a lot of time making up the names and attributes of these hypothetical worlds. Niven did just that with his Known Space stories, in which many of the planets had outlandish characteristics, such as very high gravity (Jinx) or an extremely dense atmosphere (Mount Lookitthat). In the early eighties, when I started writing in earnest, there were no real constraints on what such alien solar systems might look like. We had detected no planets around other stars, and the general view was that such work was far beyond the current capabilities of astronomers. It turned out not to be the case, though: detecting alien planets, although difficult, required only a clever upgrading of existing methodologies. By the nineties, planets were being discovered with some regularity, and we now know of thousands of them, including many cases of multiple planets around the same star. In some instances, our observations have begun to put limits on the numbers and properties of planets around familiar, SF-friendly stars such as Epsilon Eridani. It may well turn out that what was perfectly reasonable speculation thirty years ago is now ruled out by current data.

Still, let's assume for now that our real stars and imagined planets remain viable locations, and we wish to use them in new stories. That's where an additional wrinkle comes in: it's very easy to look up how far away these stars are, and on that basis, work out (depending on the mechanics of your imagined space technology) how long it would take to get there from Earth. But sooner or later your story may depend on getting from star A to star B, without stopping off at Earth en-route. How do we work out how far these stars are from each other?

All the information we need is present: for any given star, all we need are its coordinates in the night sky, and a figure for its distance. In the case of stars, those coordinates are given in somewhat unfamiliar terms: Right Ascension and Declination. Beneath the terminology, though, lies a very simple and intuitive idea. Think of a tank (or a Dalek, if so preferred). The tank can swivel its turret through a circle (or the Dalek can spin on its base), and it can raise and lower its gun barrel (or eye-stalk). The Right Ascension is the amount of swivel, and the Declination is the amount of elevation of the barrel. With those two numbers (and assuming that the barrel can point down as well as up) there's no part of the sky that the tank can't aim at. That gives you a direction to point in, and the distance tells you how far along that line that star lies. At which point, the star's position is determined in three-dimensional space. This is a spherical coordinate system, though, and (certainly for me) if I'm going to calculate the distance between two points, I'd far rather do so in the familiar Cartesian space of x, y and z.

Fortunately, we can easily convert from spherical to x,y,z coordinates, using some simple trigonometric relations. For a pair of stars, we can work out their individual positions and then use Pythagoras to work out the distance between them. It's fiddly and time-consuming, though, and far better done with a small computer program.

I wrote such a program a long, long time ago, back when I was a working scientist and wrote software (in Fortran, C or Perl) almost every day. and almost always in a Unix environment. I left science in 2004, however, and since then I have written exactly one program: an incredibly simple Arduino script to make the navigation lights on my Starship Enterprise flash on and off. Not only do I not have the old program for stellar distances, I wouldn't know what to do with it if I did. My working environment now is exclusively Windows, not Unix.

I was pleased, therefore, to find that I could still write, compile and run a Fortran program on my laptop. I downloaded the Simply Fortran package from Approximatrix and found that, allowing for my rustiness, I was still able to cobble together what I needed within a few hours of head-scratching.

I wrote a simple program called "Stars" which takes the Right Ascension, Declination and distance of any given pair of objects and outputs the distance between them in light years. There's nothing at all clever about it but there's still plenty of room for error: just because a program compiles and executes doesn't mean it's giving you sensible results. Back in my science days we'd always talk about "sanity checks": putting inputs into programs which ought to give predictable results; the kinds of special cases that you can check for yourself in your head or with simple pen and paper calculation.

One such case is easy: put one of the star's distances in as zero. You are essentially defining it as the Sun (the RA and Dec don't matter) and any outputted distance for the pair of stars ought to be the canonical distance to the other one of your objects. This all checked out. I also did some simple tests where the test-case stars were symmetrically opposed so that the distances could be calculated using simple trigonometric rules - again, all looked good. I also double-checked some of the distances as given in the later Revelation Space books, and found that all looked sensible. But I still wasn't intuitively satisfied that my program was running correctly, and decided a further check was needed.

Here we turn to the exciting world of cardboard and glue, and I made a simple model:

The circular bit is the Right Ascension plane, subdivided into ten degree quadrants. I marked out three radial distances at 5, 10 and 15 light years, on a scale of 1cm per light year.

The apexes of the four triangles - three big ones and one very long, low one - mark the positions of individual stars. These were made using a protractor and ruler, using the declination and distance values, and then glued in place at the appropriate relative positions using the RA value. For the sake of construction these stars are all in the northern hemisphere, but if their declinations were negative, they would simply project below the circle. Since the ruling scale is 1cm per light year, the distances between any two stars can now be estimated simply by holding a ruler between two apexes, and a "sanity check" made on the program. I was pleased to see that the outputted results all agreed with the ruler, to within about half a cm - consistent with the tolerances of my model, cardboard not being known for its precision engineering properties.

While it would be very nice to check the case of the distance between two real stars with positive and negative declinations, I'd need to punch a hole in the RA plane to do that. However, at this point I have enough confidence to trust that my program is behaving sensibly.

Thursday 12 December 2019

Saturday 7 December 2019

Lost Doctor Who episodes uncovered

Tardis interior still from "The Two Masters", originally transmitted 5/12/72. Unlike most of the lost recordings, this one was deliberately wiped because it was depressing and shit.

In other news, I have a short piece in The Guardian today, on interstellar visitors:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/dec/07/space-invaders-best-books-interstellar-arrivals

A couple of errors crept into the text during sub-editing - Oumuamua is most likely an asteroid, not a comet, and solar systems have biochemistry, not stars. I sent back a corrected text but they still ran the version with the errors.

Wednesday 4 December 2019

Enjoy the Silence

My third "Revenger" novel, BONE SILENCE, is now in production for an intended publication in the UK on January 30th. I'm pleased to say that an American edition will follow in April. It's a much longer novel than its predecessors, I have to say, but there's a lot in it and it does round off this particular set of adventures in the lives of the Ness sisters. Some, but not all, of the mysteries hinted at in the first two novels are resolved. I have greatly enjoyed exploring this setting, with its thousands of little worlds and age-of-sail aesthetic, and I would hope to revisit it at some point. That won't be for a little while, though, as there are other books in need of writing.

Since the summer, when I delivered BONE SILENCE (or BS, as I was about to write), I've been at work on two projects. One was the short story I mentioned in "Recent Things" back in October, which has also now been proofread, and the other is my next novel, which is a return to the setting of REVELATION SPACE. Next year will be the twentieth anniversary of that novel, astonishingly. In fact, advance reader copies were kicking around at the end of 1999, and the book itself appeared early in the year. Is it really twenty years? Yes. Deal with it, Reynolds.

As always, I'll say very little about the book-in-progress until much later in its gestation, other than to say that it is not a Prefect Dreyfus title.

Monday 11 November 2019

Science Cafe - BBC Radio Wales

Here's a link to a radio discussion I took part in a month or so ago, but which has only now gone live. It was very enjoyable, and I hope you agree that the conversation got into some interesting depth about science fiction and genre boundaries, given the time available. Listen to the piece to find out about our choices for personal favorite SF films - one each from the 50s, 80s and 90s.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000b0l8

"From urban dystopias to alien invasions, Adam Walton talks science fiction cinema with Dr Amanda Rees, whose research includes the history of science and history of the future, Dr Edward Gomez, an astronomer and honorary lecturer at Cardiff University and well-known science fiction author, Alastair Reynolds."

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000b0l8

"From urban dystopias to alien invasions, Adam Walton talks science fiction cinema with Dr Amanda Rees, whose research includes the history of science and history of the future, Dr Edward Gomez, an astronomer and honorary lecturer at Cardiff University and well-known science fiction author, Alastair Reynolds."

Tuesday 5 November 2019

Coming soon to a post-Brexit dystopia near you:

Look out for this next year.

It's good.

Very good.

http://www.newconpress.co.uk/info/book.asp?id=151&referer=Catalogue

It's good.

Very good.

http://www.newconpress.co.uk/info/book.asp?id=151&referer=Catalogue

Thursday 3 October 2019

Ad Astra

As a piece of cinematic spectacle, I found Ad Astra to be very impressive, with convincing effects and some gorgeously rendered space vistas, underpinned by a powerful Max Richter score. The acting is good, even if some of the cast are under-used, and the film has to be admired for its relative sense of restraint.

From a scientific point of view, though, it was incredibly frustrating. I wouldn't quibble if this was a Star Wars or Guardians of the Galaxy film, but at every step Ad Astra seemed to want to us to believe that it was a thoroughly authentic portrayal of near-future space travel, with all the attendant hazards. The director, James Gray, even stated that he wanted the film to be the most realistic such depiction ever made.

Unfortunately, very little about the film makes any sort of scientific or astronautical sense, from the very first scene on.

We meet Brad Pitt's character aboard a vast structure rising high in the Earth's atmosphere - a huge communications antenna focused on the search for extraterrestrial life. Nothing about this structure has any logic to it, though. It doesn't seem to be an optical array, so what is it? If it's based around radio reception, there's no advantage in height: it's the reason that radio astronomy facilities are sprawling complexes built at ground-level, often in deserts. There is an advantage in height for optical astronomy, but if you're going half-way out of the atmosphere, you might as well go all the way into orbit or indeed beyond. If the detector is designed to pick up high-energy radiation, such as X-rays, it needs to be entirely located in space or it won't work at all.

Secondly, how is it standing up? Tall structures are under an immense compressive load. Yet what we see of the antenna suggests that it's bolted together from numerous airy modular cylindrical components, exactly like the International Space Station. That's a valid engineering approach for a free-flying weightless structure, but not a vertical object still feeling Earth's gravity. If anything, this antenna - even of there was a sensible reason to build it - ought to look like the Burj Khalifa on steroids.

So why does it look like it's made from bits of the ISS? I think that's because, in those early scenes, all the film makers are really interested in is a bit of bait and switch - let's set up the scene as if it's happening in space (astronaut proceeding through airlock, onto outside of structure) and then flip our perspectives so that we suddenly realise we''re on a building, not an orbital station, and then Brad Pitt can get to do a parachute jump off it.

Things settle down for a bit as the film gets into its stride and we learn a bit of backstory about Brad and his father. Soon, though, the duff science rears its head again. It turns out that the father was on an expedition to Neptune to do more alien-intelligence studies, because - hey - Neptune is a great place to do SETI studies. Except it isn't, because Neptune, contrary to what the film tells us, is not on or near the edge of the Heliosphere, which lies at least 100 AU from the Sun, more than three times further out than Neptune. Neptune is also a planet, and planets have moons and storms and magnetospheres and so on. If you're capable of going all that distance about from the Sun, and your main objective is ending up in a low-electromagnetic noise observational environment, why would you head to a planet in the first place? I'll give this latter point a nod as maybe there were some other mission objectives that we don't hear about, but all the same - Neptune is not, a priori, a particularly great place to go looking for alien intelligence, other than providing something to orbit around.

It's when we learn that the vanished ship around Neptune has been causing electromagnetic storms on Earth that the film really lost me. Clearly, the writers had no clue how to science-up this lunacy in a way that made it even vaguely plausible. There's some mumbo-jumbo about matter-antimatter reactions on the ship going out of control, which are in turn exerting some influence on Neptune, causing it to spit out these storms ... which then intensify on their way to Earth. This is crackers, though, because even if there was some means by which a malfunctioning ship could somehow "excite" Neptune in this way - and keep in mind this is the "near future"! - and secondly because, as a rule of thumb, nothing in space ever intensifies once it's left its point of origin. Instead, things weaken and disperse with distance. It's why our eyeballs don't melt when we look at stars.

But you can see why the writers had to throw that bit of crackpot physics into the mix, as it's the only get-out clause for the later problem of explaining how Brad Pitt is able to get anywhere near this malfunctioning matter-antimatter energy source. In a logical universe, the energies would get stronger nearer the source, rather than further away from it, so Brad would be crisped long before he ever gets aboard the vanished ship.

That's probably the most egregious example of bad - or non-existent - science in the film, but hardly any scene went by without at least one questionable statement or effects point. Let's consider the initial plot driver, for instance. After being debriefed by Space Command, Brad is required to send a signal out to Neptune to persuade his father to stop with the storms, or something. The military don't know where the ship is, or even if his father is still alive, but once this message is sent they'll be able to "track it" to its point of origin. So how does that work, exactly? Once a message is transmitted, it's just a string of electromagnetic waves sailing off into deep space. It's not "trackable", as if it's got an RFID tag on it. Perhaps they're hoping to pick up an electronic signature indicating receipt of the message, sort of like how a base station can pick up a cellphone's location? Perhaps ... just possibly. But what would motivate Brad Pitt's father to allow such a detection, given that he's been hiding out in deep space for decades? If he has the means or desire to contact Earth, wouldn't he have done so already? If he doesn't want contact, all he has to do is turn off all the signalling systems on his ship.

For hand-wavey reasons, Brad can't just transmit the signal from Earth - he's got to all the way out to Mars to do it. This involves, initially, a trip to the Moon, which is actually very well staged and (for my money) easily the most impressive part of the film, with the main Lunar complex being a convincingly over-commercialised hell-hole, like an airport terminal gone mad. Quickly, though, we're back into questionable science territory. The launch pad for the Mars crossing is described as being on the "far side" of the Moon, which is fine - at least they didn't say "dark side" - but the means of getting there is absolutely nuts. They get into little lunar buggies and set off! This is as if Brad Pitt landed at the Kennedy Space Centre, and was told that he needed to get to Houston for the next rocket, and they all get into jeeps. This only makes any sort of sense if "the far side" is only, at best, a few tens of kilometres away from the main base.

Kurbrick got this right 50 years ago. The Moon is indeed smaller than Earth, but it's still bigger than the surface area of Africa. For any sort of long-range journey, it would only make sense to use some sort of low-flying spacecraft/hopper type vehicle. Hell, even UFO got that right! Driving is madness. It's even more madness to go out in flimsy, skeletal buggies in which the passengers have to wear Apollo-type spacesuits for the whole journey. Let's hope none of them get itchy noses in the days and days it'll take to drive to the other rocket.

It was at this point that I realised that much of the film's design aesthetic - not to mention its entire plot logic - is constrained by a deep fear of the future. The film is set far enough from now that an adult character (if I'm remembering rightly) has been born on Mars so unless we're in an alternate timeline, we must be in the 2050s or even 60s.

And yet at every step the film shies away from any sense of futurity.

Brad Pitt's spacesuit is pure Apollo/shuttle era - it looks nothing like the next-generation suits already on various space agency drawing boards. The rockets all look like Apollo-era tech, scaled up a little. The interiors are messy and functional, like the ISS - even when the spacecraft is supposedly a commercial operation run by Virgin Atlantic. Again, Kubrick got this right. The lunar buggies make no sense as a means for travelling on the Moon, but they are very obviously derived from the Apollo rovers. They look nothing like any of the concepts I've seen for next-generation Lunar or Martian rovers, most of which seem to (sensibly) allow for a pressurised cabin.

There's lot's more to say, but I think I've probably made my point - this is a terrible film from a standpoint of any sort of scientific or astronautical rigour.

But it is very nice to look at.

From a scientific point of view, though, it was incredibly frustrating. I wouldn't quibble if this was a Star Wars or Guardians of the Galaxy film, but at every step Ad Astra seemed to want to us to believe that it was a thoroughly authentic portrayal of near-future space travel, with all the attendant hazards. The director, James Gray, even stated that he wanted the film to be the most realistic such depiction ever made.

Unfortunately, very little about the film makes any sort of scientific or astronautical sense, from the very first scene on.

We meet Brad Pitt's character aboard a vast structure rising high in the Earth's atmosphere - a huge communications antenna focused on the search for extraterrestrial life. Nothing about this structure has any logic to it, though. It doesn't seem to be an optical array, so what is it? If it's based around radio reception, there's no advantage in height: it's the reason that radio astronomy facilities are sprawling complexes built at ground-level, often in deserts. There is an advantage in height for optical astronomy, but if you're going half-way out of the atmosphere, you might as well go all the way into orbit or indeed beyond. If the detector is designed to pick up high-energy radiation, such as X-rays, it needs to be entirely located in space or it won't work at all.

Secondly, how is it standing up? Tall structures are under an immense compressive load. Yet what we see of the antenna suggests that it's bolted together from numerous airy modular cylindrical components, exactly like the International Space Station. That's a valid engineering approach for a free-flying weightless structure, but not a vertical object still feeling Earth's gravity. If anything, this antenna - even of there was a sensible reason to build it - ought to look like the Burj Khalifa on steroids.

So why does it look like it's made from bits of the ISS? I think that's because, in those early scenes, all the film makers are really interested in is a bit of bait and switch - let's set up the scene as if it's happening in space (astronaut proceeding through airlock, onto outside of structure) and then flip our perspectives so that we suddenly realise we''re on a building, not an orbital station, and then Brad Pitt can get to do a parachute jump off it.

Things settle down for a bit as the film gets into its stride and we learn a bit of backstory about Brad and his father. Soon, though, the duff science rears its head again. It turns out that the father was on an expedition to Neptune to do more alien-intelligence studies, because - hey - Neptune is a great place to do SETI studies. Except it isn't, because Neptune, contrary to what the film tells us, is not on or near the edge of the Heliosphere, which lies at least 100 AU from the Sun, more than three times further out than Neptune. Neptune is also a planet, and planets have moons and storms and magnetospheres and so on. If you're capable of going all that distance about from the Sun, and your main objective is ending up in a low-electromagnetic noise observational environment, why would you head to a planet in the first place? I'll give this latter point a nod as maybe there were some other mission objectives that we don't hear about, but all the same - Neptune is not, a priori, a particularly great place to go looking for alien intelligence, other than providing something to orbit around.

It's when we learn that the vanished ship around Neptune has been causing electromagnetic storms on Earth that the film really lost me. Clearly, the writers had no clue how to science-up this lunacy in a way that made it even vaguely plausible. There's some mumbo-jumbo about matter-antimatter reactions on the ship going out of control, which are in turn exerting some influence on Neptune, causing it to spit out these storms ... which then intensify on their way to Earth. This is crackers, though, because even if there was some means by which a malfunctioning ship could somehow "excite" Neptune in this way - and keep in mind this is the "near future"! - and secondly because, as a rule of thumb, nothing in space ever intensifies once it's left its point of origin. Instead, things weaken and disperse with distance. It's why our eyeballs don't melt when we look at stars.

But you can see why the writers had to throw that bit of crackpot physics into the mix, as it's the only get-out clause for the later problem of explaining how Brad Pitt is able to get anywhere near this malfunctioning matter-antimatter energy source. In a logical universe, the energies would get stronger nearer the source, rather than further away from it, so Brad would be crisped long before he ever gets aboard the vanished ship.

That's probably the most egregious example of bad - or non-existent - science in the film, but hardly any scene went by without at least one questionable statement or effects point. Let's consider the initial plot driver, for instance. After being debriefed by Space Command, Brad is required to send a signal out to Neptune to persuade his father to stop with the storms, or something. The military don't know where the ship is, or even if his father is still alive, but once this message is sent they'll be able to "track it" to its point of origin. So how does that work, exactly? Once a message is transmitted, it's just a string of electromagnetic waves sailing off into deep space. It's not "trackable", as if it's got an RFID tag on it. Perhaps they're hoping to pick up an electronic signature indicating receipt of the message, sort of like how a base station can pick up a cellphone's location? Perhaps ... just possibly. But what would motivate Brad Pitt's father to allow such a detection, given that he's been hiding out in deep space for decades? If he has the means or desire to contact Earth, wouldn't he have done so already? If he doesn't want contact, all he has to do is turn off all the signalling systems on his ship.

For hand-wavey reasons, Brad can't just transmit the signal from Earth - he's got to all the way out to Mars to do it. This involves, initially, a trip to the Moon, which is actually very well staged and (for my money) easily the most impressive part of the film, with the main Lunar complex being a convincingly over-commercialised hell-hole, like an airport terminal gone mad. Quickly, though, we're back into questionable science territory. The launch pad for the Mars crossing is described as being on the "far side" of the Moon, which is fine - at least they didn't say "dark side" - but the means of getting there is absolutely nuts. They get into little lunar buggies and set off! This is as if Brad Pitt landed at the Kennedy Space Centre, and was told that he needed to get to Houston for the next rocket, and they all get into jeeps. This only makes any sort of sense if "the far side" is only, at best, a few tens of kilometres away from the main base.

Kurbrick got this right 50 years ago. The Moon is indeed smaller than Earth, but it's still bigger than the surface area of Africa. For any sort of long-range journey, it would only make sense to use some sort of low-flying spacecraft/hopper type vehicle. Hell, even UFO got that right! Driving is madness. It's even more madness to go out in flimsy, skeletal buggies in which the passengers have to wear Apollo-type spacesuits for the whole journey. Let's hope none of them get itchy noses in the days and days it'll take to drive to the other rocket.

It was at this point that I realised that much of the film's design aesthetic - not to mention its entire plot logic - is constrained by a deep fear of the future. The film is set far enough from now that an adult character (if I'm remembering rightly) has been born on Mars so unless we're in an alternate timeline, we must be in the 2050s or even 60s.

And yet at every step the film shies away from any sense of futurity.

Brad Pitt's spacesuit is pure Apollo/shuttle era - it looks nothing like the next-generation suits already on various space agency drawing boards. The rockets all look like Apollo-era tech, scaled up a little. The interiors are messy and functional, like the ISS - even when the spacecraft is supposedly a commercial operation run by Virgin Atlantic. Again, Kubrick got this right. The lunar buggies make no sense as a means for travelling on the Moon, but they are very obviously derived from the Apollo rovers. They look nothing like any of the concepts I've seen for next-generation Lunar or Martian rovers, most of which seem to (sensibly) allow for a pressurised cabin.

There's lot's more to say, but I think I've probably made my point - this is a terrible film from a standpoint of any sort of scientific or astronautical rigour.

But it is very nice to look at.

Wednesday 2 October 2019

Recent things

I'm pleased to have sold a new story, "Polished Performance", to Jonathan Strahan's forthcoming anthology of robot stories, Made to Order, which will appear in 2020.

Although it's a relatively short 7500 words, it remains the only piece of short fiction I've completed since Permafrost, itself a novella. Once I had Permafrost off my desk, I dived into the third Revenger book, Bone Silence, and that took care of all my writing for the rest of 2018 and a serious chunk of 2019 as well. The novel was delivered earlier in the summer and has now gone through the first

round of editorial revisions. Truth to tell, it was a much harder book to finish than I'd anticipated, especially so given that I thought I was nearly done with it at the end of last year.

My summer reading (other than science magazines) has been sporadic. I very much enjoyed Jonathan Coe's fine Brexit-themed novel Middle England, and I raced through heart surgeon Stephen Westaby's second book of medical essays, The Knife's Edge. In science fiction, I thoroughly recommend Peter Hamilton's forthcoming Salvation Lost, which builds on its predecessor Salvation very successfully, and is properly thrilling and scary in all the right places, as well as playing on a very expansive and ambitious future canvas.

That's it for now; I'll aim to have more to say about Bone Silence later in the year, but in the meantime I thought a brief status update was better than none at all.

best,

Al R

Although it's a relatively short 7500 words, it remains the only piece of short fiction I've completed since Permafrost, itself a novella. Once I had Permafrost off my desk, I dived into the third Revenger book, Bone Silence, and that took care of all my writing for the rest of 2018 and a serious chunk of 2019 as well. The novel was delivered earlier in the summer and has now gone through the first

round of editorial revisions. Truth to tell, it was a much harder book to finish than I'd anticipated, especially so given that I thought I was nearly done with it at the end of last year.

My summer reading (other than science magazines) has been sporadic. I very much enjoyed Jonathan Coe's fine Brexit-themed novel Middle England, and I raced through heart surgeon Stephen Westaby's second book of medical essays, The Knife's Edge. In science fiction, I thoroughly recommend Peter Hamilton's forthcoming Salvation Lost, which builds on its predecessor Salvation very successfully, and is properly thrilling and scary in all the right places, as well as playing on a very expansive and ambitious future canvas.

That's it for now; I'll aim to have more to say about Bone Silence later in the year, but in the meantime I thought a brief status update was better than none at all.

best,

Al R

Thursday 5 September 2019

Wednesday 24 July 2019

What the IF

Last week I had the great pleasure of taking part in the excellent What the IF podcast, hosted by Philip Shane and Matt Stanley. The starting point for our discussion was my story "Different Seas", which appeared in MIT Press's Twelve Tomorrows anthology, and the immersive telepresence technology that the story features.

Here's a link to the What the IF homepage:

and here's a direct link to my episode:

Thanks, Philip and Matt, for making it such fun.

If you'd like to catch up on the original story, here's a link to the MIT Press page for the book:

Tuesday 23 July 2019

Vassal states

Far from being a "vassal state" of the EU, as Boris Johnson would have it, it increasingly feels to me as if the UK is a vassal state of Eton. Who was the architect of the referendum? A gammon-faced Etonian. Who were some of the strongest voices behind the leave campaign? Etonians. Who's just slimed his way to the top of the pole? An Etonian. I write in advance of Boris Johnson's coronation but there seems no chance at all that he will not be selected.

For one brief shining moment I thought that the principled, articulate Rory Stewart (privately educated again, but not actually an Etonian - you take what you can get) might have been in with a chance, but alas, it was not to be.

Stewart not withstanding, is there not a case for banning the privately educated from high office? They have enough opportunities in life as it is. Why must they run the country as well?

For one brief shining moment I thought that the principled, articulate Rory Stewart (privately educated again, but not actually an Etonian - you take what you can get) might have been in with a chance, but alas, it was not to be.

Stewart not withstanding, is there not a case for banning the privately educated from high office? They have enough opportunities in life as it is. Why must they run the country as well?

Tuesday 16 July 2019

Saturn V

Those of you who were reading my blog ten years ago (back when it was "Teahouse on the Tracks") may remember that I decided to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of Apollo 11 by building a Saturn V rocket.

I started with the 1/96th scale Revell kit, re-released in 2009! It's actually about as old as the Apollo program itself, and because it was tooled-up slightly ahead of the missions themselves, it's supposedly not quite accurate for Apollo 11.

Looks good enough to me, though:

Although I build the kit exactly as it came out of the box, I did have some reference photos to go by, taken during a visit to KSC in 2008:

It was fun to compare and contrast with the kit as I assembled the stages, starting at the bottom and working up:

My intention had been to complete the model by July 20 2009, but that was a little optimistic. What I did achieve was all the outside bits of the Saturn V, but large areas were left unpainted. Still, it looked impressive enough:

I'd like to say that I cracked on and finished the Saturn V that summer, but I didn't. In fact, once I got it to the stage in the above picture, I was quite happy for it to sit on my desk and there matters rested for a good few years - in fact, quite a large chunk of the decade between then and now.

Two or three years ago I did complete the rocket, however - well nearly. I assembled and painted lunar module, and completed all the exterior painting of the Saturn stack, and did all the engines and fuel tanks. But there are still a few decals to be added to the LM. Perhaps I'll get around to them somewhere between now and the sixtieth anniversary...

The model as it stands today, July 16th 2019:

I started with the 1/96th scale Revell kit, re-released in 2009! It's actually about as old as the Apollo program itself, and because it was tooled-up slightly ahead of the missions themselves, it's supposedly not quite accurate for Apollo 11.

Looks good enough to me, though:

Although I build the kit exactly as it came out of the box, I did have some reference photos to go by, taken during a visit to KSC in 2008:

It was fun to compare and contrast with the kit as I assembled the stages, starting at the bottom and working up:

My intention had been to complete the model by July 20 2009, but that was a little optimistic. What I did achieve was all the outside bits of the Saturn V, but large areas were left unpainted. Still, it looked impressive enough:

I'd like to say that I cracked on and finished the Saturn V that summer, but I didn't. In fact, once I got it to the stage in the above picture, I was quite happy for it to sit on my desk and there matters rested for a good few years - in fact, quite a large chunk of the decade between then and now.

Two or three years ago I did complete the rocket, however - well nearly. I assembled and painted lunar module, and completed all the exterior painting of the Saturn stack, and did all the engines and fuel tanks. But there are still a few decals to be added to the LM. Perhaps I'll get around to them somewhere between now and the sixtieth anniversary...

The model as it stands today, July 16th 2019:

Monday 15 April 2019

Gene Wolfe 1931 - 2019

Gene Wolfe has died.

I feel I ought to say more, but it's late and I'm tired. I'll leave it with this: it took me years to find a way into his work, but once I did, I was never the same again. He changed me as a writer and, I think, a human being. I never met him properly (although we did once participate in a panel via video link) but I got to write about him a few times, and his passing leaves us immeasurably poorer.

Thank you, Mr Wolfe.

I feel I ought to say more, but it's late and I'm tired. I'll leave it with this: it took me years to find a way into his work, but once I did, I was never the same again. He changed me as a writer and, I think, a human being. I never met him properly (although we did once participate in a panel via video link) but I got to write about him a few times, and his passing leaves us immeasurably poorer.

Thank you, Mr Wolfe.

Tuesday 9 April 2019

Titans of Sci-Fi event

On the 18th of April I'll be in Waterstones Picadilly in London, talking SF with Temi Oh and Emma Newman, with Pat Cadigan (rather than Gavin Smith as originally announced) chairing our conversation.I thoroughly enjoyed Planetfall, Emma's first SF novel (and am now catching up with her other works, including the newly-released Atlas Alone) and I was greatly impressed with Temi's debut, which is a powerful meditation on the consequences of leaving home. Decades-long interstellar voyages feature in both their works, as well as mine, so we should have plenty to talk about.

https://www.waterstones.com/events/titans-of-sci-fi-alastair-reynolds-emma-newman-and-temi-oh-in-conversation-with-gavin-smith/london-piccadilly

"Emma Newman is the author of Planetfall, After Atlas, Before Mars and Atlas Alone. She is also a professional audiobook narrator, and co-writes and hosts a Huge nominated podcast called Tea & Jeopardy.

Temi Oh is the debut author of Do You Dream of Terra-Two? Having studied Neuroscience, Temi has written on topics ranging from Philosophy of the Mind to Space Physiology. She has also ran a book-group called “Neuroscience-fiction,” leading discussions about science-fiction books which focus on the brain."

Monday 25 March 2019

Thursday 21 March 2019

Tuesday 19 March 2019

Out now

Permafrost, my new novella from Tor books, is published today.

Here's the description:

Fix the past. Save the present. Stop the future. Master of science fiction Alastair Reynolds unfolds a time-traveling climate fiction adventure in Permafrost.

2080: at a remote site on the edge of the Arctic Circle, a group of scientists, engineers and physicians gather to gamble humanity's future on one last-ditch experiment. Their goal: to make a tiny alteration to the past, averting a global catastrophe while at the same time leaving recorded history intact. To make the experiment work, they just need one last recruit: an ageing schoolteacher whose late mother was the foremost expert on the mathematics of paradox.

2028: a young woman goes into surgery for routine brain surgery. In the days following her operation, she begins to hear another voice in her head... an unwanted presence which seems to have a will, and a purpose, all of its own ? one that will disrupt her life entirely. The only choice left to her is a simple one.

Does she resist ... or become a collaborator?

To reiterate, this is a novella, not a novel, so you're getting around 34,000 words of fiction, spread over about 180 pages. Were you so inclined, you could easily read it in a long sitting. I mention this because (based on prior experience) there do always seem to be some readers who expect a novel's worth of content from what is clearly marketed as a novella, and feel disgruntled when the actuality fails to meet their expectations. (These categories are somewhat arbitrary, and definitions vary, but as far as the majority of SF readers are concerned, a novella lies somewhere between 17,500 and 40,000 words. My earlier story Slow Bullets was about 45,000 words in its initial form, but we very deliberately reduced it to a shade under 40,000 just so there'd be no ambiguity about its nature.) So, please, be aware that what you're getting here is equivalent to around six or seven short stories, and perhaps a third of a typical novel, and about a tenth of a big fat doorstopper.

Writing in Locus, Liz Bourke called the story elegant, and described it as an enjoyable, engaging and thought-provoking novella, while also saying that she found the handling of time travel original. In Library Journal, Tina Panik called it "outstanding" and compared it to Jeff Vandermeer's Southern Reach trilogy.

Here's a link to Tor's page for the book:

https://publishing.tor.com/permafrost-alastairreynolds/9781250303554/

And Barnes and Noble:

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/permafrost-alastair-reynolds/1129556876?ean=9781250303561#/

And Wordery:

https://wordery.com/permafrost-alastair-reynolds-9781250303561?cTrk=MTQyMjMxMzIwfDVjOTBmOWRhMTdmMzM6MToxOjVjOTBmOWQwMjkwNmQxLjgwMTQ2NjQxOjViMjIyYmQ3

Other retailers are available.

Al

Here's the description:

Fix the past. Save the present. Stop the future. Master of science fiction Alastair Reynolds unfolds a time-traveling climate fiction adventure in Permafrost.

2080: at a remote site on the edge of the Arctic Circle, a group of scientists, engineers and physicians gather to gamble humanity's future on one last-ditch experiment. Their goal: to make a tiny alteration to the past, averting a global catastrophe while at the same time leaving recorded history intact. To make the experiment work, they just need one last recruit: an ageing schoolteacher whose late mother was the foremost expert on the mathematics of paradox.

2028: a young woman goes into surgery for routine brain surgery. In the days following her operation, she begins to hear another voice in her head... an unwanted presence which seems to have a will, and a purpose, all of its own ? one that will disrupt her life entirely. The only choice left to her is a simple one.

Does she resist ... or become a collaborator?

To reiterate, this is a novella, not a novel, so you're getting around 34,000 words of fiction, spread over about 180 pages. Were you so inclined, you could easily read it in a long sitting. I mention this because (based on prior experience) there do always seem to be some readers who expect a novel's worth of content from what is clearly marketed as a novella, and feel disgruntled when the actuality fails to meet their expectations. (These categories are somewhat arbitrary, and definitions vary, but as far as the majority of SF readers are concerned, a novella lies somewhere between 17,500 and 40,000 words. My earlier story Slow Bullets was about 45,000 words in its initial form, but we very deliberately reduced it to a shade under 40,000 just so there'd be no ambiguity about its nature.) So, please, be aware that what you're getting here is equivalent to around six or seven short stories, and perhaps a third of a typical novel, and about a tenth of a big fat doorstopper.

Writing in Locus, Liz Bourke called the story elegant, and described it as an enjoyable, engaging and thought-provoking novella, while also saying that she found the handling of time travel original. In Library Journal, Tina Panik called it "outstanding" and compared it to Jeff Vandermeer's Southern Reach trilogy.

Here's a link to Tor's page for the book:

https://publishing.tor.com/permafrost-alastairreynolds/9781250303554/

And Barnes and Noble:

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/permafrost-alastair-reynolds/1129556876?ean=9781250303561#/

And Wordery:

https://wordery.com/permafrost-alastair-reynolds-9781250303561?cTrk=MTQyMjMxMzIwfDVjOTBmOWRhMTdmMzM6MToxOjVjOTBmOWQwMjkwNmQxLjgwMTQ2NjQxOjViMjIyYmQ3

Other retailers are available.

Al

Monday 18 March 2019

Happy Birthday to Me

53rd birthday present from my wife. Thanks to the nice people in PMT in Bristol who helped me try a variety of Strats before settling on this lovely specimen. I'm a lucky chap!

Sunday 10 March 2019

Love, Death & Robots

Here's a link to Netflix's own page for the series:

Be warned that the trailers are very much Not Safe For Work. There's a lot more out there if you're prepared to dig around, including some mini-trailers for the individual stories.

The series premiers on March 15th.

Wednesday 27 February 2019

Stay Frosty

Ahead of the publication of my new time-travel novella Permafrost later in March, Tor.com have put up an excerpt from the story. Head on over to Tor.com to take a look, if you're so inclined.

https://www.tor.com/2019/02/27/excerpts-permafrost-alastair-reynolds/

https://www.tor.com/2019/02/27/excerpts-permafrost-alastair-reynolds/

Tuesday 26 February 2019

Mark Hollis

Few bands meant more to me in the Eighties than Talk Talk, so I was very saddened to learn of the death of Mark Hollis, who was both the singer and the main creative force behind the group.

I took a interest in them around the time of their second album, but it was the third - 1986's The Colour of Spring - which really convinced me that there was something interesting and innovative going on:

I bought this album - the cover art is by James Marsh, who also did a slew of JG Ballard editions around the same time - within a day or two of its release in March, taped it, and then took the cassette back with me to university. I played little else that term, and the music was a perfect accompaniment to the gradual shift of seasons from winter into spring. Nobody else was making music that sounded anything like Talk Talk at the time. After the clever, driving synth-pop of their first two records, this album was a swerve into analog minimalism, weirdly forward-looking at the same time that it harked back to the musical textures of the sixties and seventies, evoking Traffic, Procul Harum and so on with Mellotrons and organs in sharp counterpoint to the typical sequenced excess of mid-eighties chart material. A great deal of music recorded at this time hasn't worn well, due to heavv-handed production and an over-use of drum machines, keyboards and assorted in-vogue effects, but Talk Talk's records still sound timeless. I bought The Colour of Spring against the advice of music reviewers, incidentally, who gave the album rather lukewarm notices. They couldn't have been more wrong.

I saw Talk Talk in concert in Newcastle town hall that same year, and I followed them through the rest of their career - into the increasing starkness of their subsequent two albums, and the almost unbearable melancholy of Mark Hollis's one solo record. And that was it. Talk Talk ceased to exist; Mark Hollis stopped making music almost completely, preferring the sanity of a family life over the serial indignities of the music business. I'd read the occasional interview or article over the ensuing years, and had come to the conclusion that it was very unlikely we'd ever see any more recordings from Hollis, under any banner. Six albums worth - plus a few extras - hardly amounts to an afternoon's listening. It would be churlish to complain, though, given the quality of the music, the care with which it was created, and the quietly influential reach it's had in the ensuing decades. We could have done a lot worse.

Oh, and I liked Talk Talk so much that one of their songs provided the last line of a novel.

Monday 4 February 2019

I have never met Napoleon

W.G. "Snuffy" Walden, incidentally, is the gentleman who did the West Wing theme tune, among many others. Hope the Dan fans among you enjoy this interlude.

Al

Saturday 2 February 2019

Tuesday 15 January 2019

13/9/99

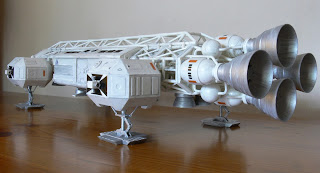

It may not have been particularly good science fiction but Space:1999 certainly had some nice spaceships. Chief among these, surely, is the iconic Eagle, which featured in every episode and still looks good and plausible today. OK, it's maybe not the ideal shape for something that was regularly seen coming and going from planets with atmospheres, but that didn't particularly bother me when I was nine.

This 1/48th model is actually the fourth Eagle that I've owned. I had two of the Dinky die-cast models which were released around the time of the original series, and later I had the Airfix kit, although I've long since lost the latter. This kit is a half-scale replica of the 22 inch studio model and is accordingly much more detailed and accurate than either its Dinky or Airfix predecessors.

In Wales, only the first season of Space:1999 was ever aired. I've still never seen the second, other than clips, which I gather is no great loss, especially as it lacked the fantastic music and opening titles of the first.

Friday 11 January 2019

Trying to give the light the slip

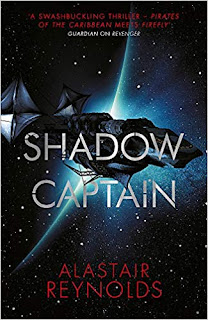

Yesterday saw the UK publication of my new novel Shadow Captain, which will be followed by the American edition in a few days.

This story is a direct follow-on from Revenger and advances the story of the Ness sisters as they come to terms with their new situation. In contrast to the first book, which was very much Arafura's account, this one is told from Adrana's point of view and I hope offers a distinctly different voice and sensibility. While the creation of any book will present its challenges, I certainly had my fair share of enjoyment in the writing, and I found it fun to dig deeper into the implied universe of the Congregation, while exploring the sisters' relationship as each confronts new challenges and difficulties. I'm now nearly done with the successor, Bone Silence, which - even if it might not be the last word on the Congregation - will wrap up this particular extended adventure in the lives of the Ness sisters.

Because I'm invested in the writing of the follow-up, and at a rather critical part of the process, I thought it might be wise to avoid reviews of this one, at least until the new book is delivered. If only I had the moral fibre. I can report that Locus liked it, as did SFX, and early reader reactions seem to be broadly positive, for which I''m grateful.

https://www.orionbooks.co.uk/books/detail.page?isbn=9780575090637

https://soundcloud.com/orionbooks/sets/shadow-captain-by-alastair-reynolds

https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/alastair-reynolds/shadow-captain/9781549171369/

In the meantime, have some musical accompaniment.

Al (wishing all the very best for 2019).

This story is a direct follow-on from Revenger and advances the story of the Ness sisters as they come to terms with their new situation. In contrast to the first book, which was very much Arafura's account, this one is told from Adrana's point of view and I hope offers a distinctly different voice and sensibility. While the creation of any book will present its challenges, I certainly had my fair share of enjoyment in the writing, and I found it fun to dig deeper into the implied universe of the Congregation, while exploring the sisters' relationship as each confronts new challenges and difficulties. I'm now nearly done with the successor, Bone Silence, which - even if it might not be the last word on the Congregation - will wrap up this particular extended adventure in the lives of the Ness sisters.

Because I'm invested in the writing of the follow-up, and at a rather critical part of the process, I thought it might be wise to avoid reviews of this one, at least until the new book is delivered. If only I had the moral fibre. I can report that Locus liked it, as did SFX, and early reader reactions seem to be broadly positive, for which I''m grateful.

https://www.orionbooks.co.uk/books/detail.page?isbn=9780575090637

https://soundcloud.com/orionbooks/sets/shadow-captain-by-alastair-reynolds

https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/alastair-reynolds/shadow-captain/9781549171369/

In the meantime, have some musical accompaniment.

Al (wishing all the very best for 2019).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)