I'm out and about in the UK quite a bit this month.

The evening of this coming Wednesday, 6th November, I'll be speaking at the Institute of Physics in Derby:

http://derbyiop.eventbrite.co.uk/

I'll also be signing at Waterstones Derby from 2 - 3 pm on the same day.

The following Thursday, 7th November, I'll be speaking at the Cambridge University Science Fiction and Fantasy Society in, unsurprisingly, Cambridge.

http://cusfs.soc.srcf.net/home

I'm not entirely sure how it works if you are not a member of the society or the university itself, I'm afraid, but I imagine they'd be welcoming. Best to phone ahead, though.

As if that wasn't enough excitement, I'll be in Nottingham a week later to talk to university's science fiction and fantasy society, on Friday 15th November. The talk is scheduled to start at 7.00pm.

http://www.su-web.nottingham.ac.uk/~scifi/

Finally, at the end of the month on Thursday 28th November I'll be in Glenrothes, Fife, talking about Doctor Who and other things:

http://www.onfife.com/events/cosmic-thrills-alastair-reynolds-rothes-halls-library

Hope to see some of you at one of these events.

Monday 4 November 2013

Thursday 17 October 2013

Newport State of Mind

This weekend I'll be participating in Space, Time, Machine and Monster, a literary festival in Newport, South Wales.

http://www.literaturewales.org/space-time-machine-and-monster/

Quoting from the website:

"Following a hugely successful first outing in Pontypridd in 2008, the Space, Time, Machine & Monster literary festival returns for two days packed full of science-fiction, fantasy and horror. Expect talks, workshops, film screenings, panel events and competitions for adults, teens and your little horrors.

Event highlights include a talk with Rhianna Pratchett on the world of narrative gaming; and Page to Screen: Sci-fi, Fantasy and Horror with Catherine Bray who is currently editor of Film4.com and a regular guest presenter on BBC1′s Film 2013 With Claudia Winkleman. Plus, discover the real science behind Doctor Who with Mark Brake and Jon Chase and explore the work of Arthur Machen and J.R.R. Tolkien with Catherine Fisher, Gwilym Games and Dimitra Fimi.

There will also be the chance to explore the world of Warhammer and take part in a series of battles waging throughout the day, or you could create your own animated alien universe, zombie comic and even your own origami Star Wars character. The programme features a top line-up of speakers, authors and illustrators including, Huw Aaron, Ben Aaronovitch, Horatio Clare, Jasper Fforde, Catherine Fisher, Gwyneth Lewis, Alastair Reynolds, Stephen Volk and many more.

Bestselling fantasy author Jasper Fforde commented: "There are clearly not enough zombies or Time Travel in South Wales, and I am delighted to see Literature Wales addressing that imbalance"

I note also that the excellent Adam Roberts will also be attending. My events are on the Saturday, and I look forward to seeing some of you there.

http://www.literaturewales.org/space-time-machine-and-monster/

Quoting from the website:

"Following a hugely successful first outing in Pontypridd in 2008, the Space, Time, Machine & Monster literary festival returns for two days packed full of science-fiction, fantasy and horror. Expect talks, workshops, film screenings, panel events and competitions for adults, teens and your little horrors.

Event highlights include a talk with Rhianna Pratchett on the world of narrative gaming; and Page to Screen: Sci-fi, Fantasy and Horror with Catherine Bray who is currently editor of Film4.com and a regular guest presenter on BBC1′s Film 2013 With Claudia Winkleman. Plus, discover the real science behind Doctor Who with Mark Brake and Jon Chase and explore the work of Arthur Machen and J.R.R. Tolkien with Catherine Fisher, Gwilym Games and Dimitra Fimi.

There will also be the chance to explore the world of Warhammer and take part in a series of battles waging throughout the day, or you could create your own animated alien universe, zombie comic and even your own origami Star Wars character. The programme features a top line-up of speakers, authors and illustrators including, Huw Aaron, Ben Aaronovitch, Horatio Clare, Jasper Fforde, Catherine Fisher, Gwyneth Lewis, Alastair Reynolds, Stephen Volk and many more.

Bestselling fantasy author Jasper Fforde commented: "There are clearly not enough zombies or Time Travel in South Wales, and I am delighted to see Literature Wales addressing that imbalance"

I note also that the excellent Adam Roberts will also be attending. My events are on the Saturday, and I look forward to seeing some of you there.

Tuesday 15 October 2013

Two Trunks

According to popular wisdom, all writers have at least one early and unpublished book that is best consigned to obscurity - the so called "trunk novel", the idea being that you keep it locked away in a trunk rather than doing the sensible thing and binning it. According to another branch of popular wisdom, the first thing writers do when they're stuck for inspiration is dust off a trunk novel and pass it off as a fresh new book. I'm sure that happens occasionally, but I suspect the truth is that most writers would rather throw themselves under a bus than see their juvenile work reaching print. More probably, I'd suggest, we look on these things as part of the necessary learning curve of becoming a fluent writer - we don't have to admire them, or even like them, but we can understand that they were an essential part of our literary development that we had to pass through. There may even be elements of these unpublished works that, with a little recasting, can still filter through into our professional work.

My two trunk novels don't live in a trunk and while they're not exactly representative of where I'm "at" as a writer in 2013, I'm certainly not ashamed of them. I keep them on the same shelves as all my other written works, and look on them with a sort of tolerant fondness. I take them to schools and libraries and pass them around. I don't have any illusions as to the quality of the books, but I am proud that I started and finished them. They were vital stepping stones on my path to becoming a published writer, and if they served one useful function, it was to cure me of any fear of The Novel.

Here they are, in exactly the same ring folders in which I started them:

Exciting, aren't they? I bet you can't wait to see what's inside those enticingly patterned covers.

Wait no more, because here are the thrilling title pages:

The uppermost book, the one in the yellow Colman's Mustard folder, is "A Union World", which I wrote between 1979 and 1982. It took a long time because whenever I got to the end of the book, I hated the start. This initiated a Forth Bridge-like process of constant revision which might have gone on forever had I not decided to finally accept the book on its own terms and stop.

When I began "A Union World", my science fiction horizons were very limited. I enjoyed TV and cinema SF, 2000AD magazine, and had read a bit of Clarke and Asimov. But I was really pretty clueless. When I finished the book, my literary tastes had widened to include the likes of Larry Niven, Harry Harrison and James White - true eclecticism, I think you'll agree. During the late revisions, indeed, I tried very hard to emulate the tone and scope of Niven's Known Space sequence. The novel deals with the human space federation making first contact with a number of different alien factions. It has colony worlds, FTL, robots, space battle fleets and so on. The plot, such as it is, revolves around a military research base on a distant colony world, which has mysteriously severed all contact with Earth. In a setup surprisingly similar to the opening act of Aliens, the Colonial forces decide to send in an assault ship full of elite soldiers to retake the base and establish what has happened, and in doing so recruit (or rather blackmail) a civilian pilot into helping them out. It turns out that the civilan's creaky old space freighter has an outmoded drive system which means it's the only ship that can enter the planet's atmosphere undetected, enabling the troops' dropship to be placed close to the compromised base. Later on we discover than an alien mastermind has taken control of the base, plans to enshroud it in a force field, and use planet-destroying bombs to literally shatter the entire rest of the planet, so that the base becomes a free-flying space fortress. This all happens! Later, predictably, there's an enormous space battle between the combine forces of Earth and the flying space fortress. There's even a space-aircraft-carrier called the Ark Royal.

The second book, entitled "Dominant Species", is of similar length and takes place in the same universe. But I wrote it in a much shorter span of time compared to the first. My recollection is that I started it very late in 1983 and finished it somewhere around the Spring of 1984 - in other words, in a few months rather than a few years. The upside of that intense burst of creativity was that the book was much more uniform in its style, and actually had a plot that made a kind of sense. The downside is that I really should have been studying for my 'A' levels in 1984, which I duly failed in spectacular fashion. But at least I had a novel to show for it.

Both books are handwritten in their entirety, on lined A4 paper, in black biro:

I've still got a bit of a thing about black biro: I can't be doing with blue at all. I also used a tankerload of Tip-Ex correction fluid, and where that wasn't practicable, I either rewrote the entire page (front and back) or glued a small insert over the offending section. Years later, I'd go through a very similar process of cutting and pasting while preparing the artwork for my PhD thesis, so the experience certainly wasn't wasted.

I shan't say too much about the second book, except that it picks up the story of the human expansion a bit later on, and there are some more aliens and giant flying space things. Neither book takes place in the Revelation Space universe, incidentally, but a lot the furniture and character names of the RS stories show up here for the first time. Most of the planet names, as well as some of what would be later be principle characters in Revelation Space such as Sajaki and Captain John Brannigan, but here in very different roles.

Speaking of which:

At the time I wrote the second book, I was heavily influenced by the "fake documents" style of Joe Haldeman's second novel, Mindbridge, and so I made up a few fake documents and logos to be inserted into the text. Looks fantastically convincing, doesn't it? I'm sure they'll still be using typewriters with sticky ribbons in 2332, and won't yet have solved that tricky "right justification" problem.

My two trunk novels don't live in a trunk and while they're not exactly representative of where I'm "at" as a writer in 2013, I'm certainly not ashamed of them. I keep them on the same shelves as all my other written works, and look on them with a sort of tolerant fondness. I take them to schools and libraries and pass them around. I don't have any illusions as to the quality of the books, but I am proud that I started and finished them. They were vital stepping stones on my path to becoming a published writer, and if they served one useful function, it was to cure me of any fear of The Novel.

Here they are, in exactly the same ring folders in which I started them:

Exciting, aren't they? I bet you can't wait to see what's inside those enticingly patterned covers.

Wait no more, because here are the thrilling title pages:

The uppermost book, the one in the yellow Colman's Mustard folder, is "A Union World", which I wrote between 1979 and 1982. It took a long time because whenever I got to the end of the book, I hated the start. This initiated a Forth Bridge-like process of constant revision which might have gone on forever had I not decided to finally accept the book on its own terms and stop.

When I began "A Union World", my science fiction horizons were very limited. I enjoyed TV and cinema SF, 2000AD magazine, and had read a bit of Clarke and Asimov. But I was really pretty clueless. When I finished the book, my literary tastes had widened to include the likes of Larry Niven, Harry Harrison and James White - true eclecticism, I think you'll agree. During the late revisions, indeed, I tried very hard to emulate the tone and scope of Niven's Known Space sequence. The novel deals with the human space federation making first contact with a number of different alien factions. It has colony worlds, FTL, robots, space battle fleets and so on. The plot, such as it is, revolves around a military research base on a distant colony world, which has mysteriously severed all contact with Earth. In a setup surprisingly similar to the opening act of Aliens, the Colonial forces decide to send in an assault ship full of elite soldiers to retake the base and establish what has happened, and in doing so recruit (or rather blackmail) a civilian pilot into helping them out. It turns out that the civilan's creaky old space freighter has an outmoded drive system which means it's the only ship that can enter the planet's atmosphere undetected, enabling the troops' dropship to be placed close to the compromised base. Later on we discover than an alien mastermind has taken control of the base, plans to enshroud it in a force field, and use planet-destroying bombs to literally shatter the entire rest of the planet, so that the base becomes a free-flying space fortress. This all happens! Later, predictably, there's an enormous space battle between the combine forces of Earth and the flying space fortress. There's even a space-aircraft-carrier called the Ark Royal.

The second book, entitled "Dominant Species", is of similar length and takes place in the same universe. But I wrote it in a much shorter span of time compared to the first. My recollection is that I started it very late in 1983 and finished it somewhere around the Spring of 1984 - in other words, in a few months rather than a few years. The upside of that intense burst of creativity was that the book was much more uniform in its style, and actually had a plot that made a kind of sense. The downside is that I really should have been studying for my 'A' levels in 1984, which I duly failed in spectacular fashion. But at least I had a novel to show for it.

Both books are handwritten in their entirety, on lined A4 paper, in black biro:

I've still got a bit of a thing about black biro: I can't be doing with blue at all. I also used a tankerload of Tip-Ex correction fluid, and where that wasn't practicable, I either rewrote the entire page (front and back) or glued a small insert over the offending section. Years later, I'd go through a very similar process of cutting and pasting while preparing the artwork for my PhD thesis, so the experience certainly wasn't wasted.

I shan't say too much about the second book, except that it picks up the story of the human expansion a bit later on, and there are some more aliens and giant flying space things. Neither book takes place in the Revelation Space universe, incidentally, but a lot the furniture and character names of the RS stories show up here for the first time. Most of the planet names, as well as some of what would be later be principle characters in Revelation Space such as Sajaki and Captain John Brannigan, but here in very different roles.

Speaking of which:

At the time I wrote the second book, I was heavily influenced by the "fake documents" style of Joe Haldeman's second novel, Mindbridge, and so I made up a few fake documents and logos to be inserted into the text. Looks fantastically convincing, doesn't it? I'm sure they'll still be using typewriters with sticky ribbons in 2332, and won't yet have solved that tricky "right justification" problem.

Wednesday 18 September 2013

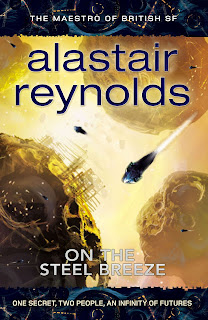

Incoming

ON THE STEEL BREEZE is only ten days from UK publication, and at least one bookseller seems to have copies in stock already, although they may not yet be for sale. Having just returned from America, and with my post still to be collected from my neighbour, it's entirely possible that there might be a finished copy in my mail as well. I'll find out soon enough. It's always a sobering moment, the first time you hold the end product. Months or years of work, distilled into a rectangle of card and paper. This is it - no more changes now.

It seems odd to have said so little about this book, but I swore some time ago that I would avoid talking it to death before publication, a trap I suspect I fell slightly into with Blue Remembered Earth. On the other hand, I'm genuinely excited to see what the world makes of it. And, of course, not a little nervous about that same reception. This is the middle book of the "Poseidon's Children" trilogy but, from my standpoint at least, it feels like quite a different book to its predecessor. In my more pretentious moments, I've suggested that this is the darker second movement of a symphony, and there's no doubt that, in parts, the book is markedly more violent and dystopian than Blue Remembered Earth. If BRE explored some unabashedly utopian ideas, then OTSB offers a sort of critique or reflection on where some of those trends might end up given another century or two of development. Yes, stuff goes wrong in this book. Bad stuff happens to people, people do bad things to each other, and there are deaths - quite a lot of them, in fact. That's not to say that it's an out-and-out dystopia, any more than the real world of 2013 is. But there's a good deal of peril, there are ominous developments, and things that we might have thought we understood at the end of BRE turn out to be ... otherwise, and not always in ways we might have wished.

I'm tempted to say more (in fact, I've just deleted a paragraph of expository waffle, telling you all about Chiku Akinya, my central character) but I shall refrain. In the meantime, the prologue and three chapters of the novel are now available to read on the Gollancz website, and here are the links:

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-1/

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-2/

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-3-and-founding-fathers-of-rocketry/

Hope you enjoy these excerpts, and (if you soldier through them) that they provide some incentive to read the whole book.

It seems odd to have said so little about this book, but I swore some time ago that I would avoid talking it to death before publication, a trap I suspect I fell slightly into with Blue Remembered Earth. On the other hand, I'm genuinely excited to see what the world makes of it. And, of course, not a little nervous about that same reception. This is the middle book of the "Poseidon's Children" trilogy but, from my standpoint at least, it feels like quite a different book to its predecessor. In my more pretentious moments, I've suggested that this is the darker second movement of a symphony, and there's no doubt that, in parts, the book is markedly more violent and dystopian than Blue Remembered Earth. If BRE explored some unabashedly utopian ideas, then OTSB offers a sort of critique or reflection on where some of those trends might end up given another century or two of development. Yes, stuff goes wrong in this book. Bad stuff happens to people, people do bad things to each other, and there are deaths - quite a lot of them, in fact. That's not to say that it's an out-and-out dystopia, any more than the real world of 2013 is. But there's a good deal of peril, there are ominous developments, and things that we might have thought we understood at the end of BRE turn out to be ... otherwise, and not always in ways we might have wished.

I'm tempted to say more (in fact, I've just deleted a paragraph of expository waffle, telling you all about Chiku Akinya, my central character) but I shall refrain. In the meantime, the prologue and three chapters of the novel are now available to read on the Gollancz website, and here are the links:

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-1/

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-2/

http://www.gollancz.co.uk/2013/09/on-the-steel-breeze-chapter-3-and-founding-fathers-of-rocketry/

Hope you enjoy these excerpts, and (if you soldier through them) that they provide some incentive to read the whole book.

Sunday 15 September 2013

Remember the Alamo

I enjoyed the World Science Fiction Convention in San Antonio. As always, I'm left with slightly mixed feelings about what I expect to get out of such a gathering, as well as what I'm actually bringing to the show by being there. But there's no doubt that from my perspective as a writer and program participant, it all seemed well organised. The convention centre was, from a British viewpoint, typically huge and at times bewildering in its layout. I never did make it to the Green Room. But the panels seemed to be well attended and judging by the feedback, enjoyed by both participants and audience members. After two attendees were not able to make it, the panel on SF art and artists as writers turned out to be just Joe Haldeman and myself, but we enjoyed ourselves and I think we kept it just the right side of self-indulgence. Luckily, because I wasn't very well prepared, Joe had brought some examples of his own art along.

I did a few other program items but the one that will stick in my memory was the panel on the legacy of Iain Banks and the Culture books. Ably moderated by Vince Docherty, the panel also included Kim Stanley Robinson, Ben Jeapes and myself. In his opening remarks, Vincent stated that a female panelist had been unable to attend, which was why Ben had come on at short notice. (For the record, I'm not hugely bothered about panel parity on a given topic provided there is a good shot at balance across a convention's entire programming track, but it was good to hear that efforts had been made). What made this panel memorable, in my view, was that for once none of us were there to promote our own works or careers - not that my fellow panelists would have been so crass as to do that anyway, but it was one hundred percent Iain and his legacy that we were there to discuss. It was an honour and a privelege and I hope we rose to the occasion. I knew Iain only slightly, as I've written elsewhere, and I don't think Ben had met him. But we had all been saddened by his death, and brought to a renewed appreciation for the huge body of work he left us. Stan Robinson, though, had known Iain much more closely, and over a much longer span of time. It was wonderful to hear Stan's thoughts on both the books and the man. SF is much the poorer for Iain's passing, a fact that I think will only become more evident as time passes.

I didn't go to the Hugo ceremony, so I missed the controversy, such as it was. My wife was in town with me, but since she did not have an attending membership, we decided to go to see a film instead - Elysium, during which I mostly slept. I couldn't summon tremendous enthusiasm for the Hugo evening anyway. Some undeniably good works were nominated, and I didn't sense any great outpouring of anger after the results. I'd have liked 2312 to do well, certainly, but John Scalzi has been such a force for good in the field, taking a genuinely heroic stand, that I doubt anyone would have much begrudged his win for Redshirts, quite aside from the fact that it had many admirers. The fact is, though, that I didn't even vote. I just couldn't summon up the enthusiasm or the energy, in a professionally difficult year in which I'd read almost nothing eligible and in which the one book I did rate highly - 2312 - was to some extent likely to overshadow my own eligible novel, Blue Remembered Earth. (Stan's is the better novel, though - go and read it). I needn't have worried, though. When the full Hugo results were made available, nothing of mine had come to close to being nominated, let alone winning. Normally there's a work or two of mine somewhere down below the cutoff, which is enough to provide some crumb of consolation, but this year there was nothing. I suppose I shouldn't be too surprised - I've made plain my thoughts on SF's year-long awards circus - but it was sobering all the same, as if my entire SF career was happening in some parallel world entirely removed from the Hugos. To be fair, I have had one Hugo nomination, for Troika back in 2011, for which I was genuinely grateful, and which is one more Nebula nomination than I've managed to notch up in 23 years of professional publishing. All of which probably sounds bitter, but actually I'm more bemused than disappointed. I do well enough commercially, and people whose opinions matter to me occasionally say nice things about my fiction. My short fiction is widely reprinted and anthologised. But the field has two conspicuous badges of merit, the Hugos and the Nebulas, and judging by those I'm just barely on the map.

Rather than end on a downbeat note, though, I'll reiterate that I enjoyed the convention very much. I appreciated the work that went in behind the scenes, and I saw a lot of people having a great time. I was personally disappointed that my friends from Helsinki did not succeed in winning their bid for 2015, but - hey - London is next. And awards or otherwise, I hope to be there.

I did a few other program items but the one that will stick in my memory was the panel on the legacy of Iain Banks and the Culture books. Ably moderated by Vince Docherty, the panel also included Kim Stanley Robinson, Ben Jeapes and myself. In his opening remarks, Vincent stated that a female panelist had been unable to attend, which was why Ben had come on at short notice. (For the record, I'm not hugely bothered about panel parity on a given topic provided there is a good shot at balance across a convention's entire programming track, but it was good to hear that efforts had been made). What made this panel memorable, in my view, was that for once none of us were there to promote our own works or careers - not that my fellow panelists would have been so crass as to do that anyway, but it was one hundred percent Iain and his legacy that we were there to discuss. It was an honour and a privelege and I hope we rose to the occasion. I knew Iain only slightly, as I've written elsewhere, and I don't think Ben had met him. But we had all been saddened by his death, and brought to a renewed appreciation for the huge body of work he left us. Stan Robinson, though, had known Iain much more closely, and over a much longer span of time. It was wonderful to hear Stan's thoughts on both the books and the man. SF is much the poorer for Iain's passing, a fact that I think will only become more evident as time passes.

I didn't go to the Hugo ceremony, so I missed the controversy, such as it was. My wife was in town with me, but since she did not have an attending membership, we decided to go to see a film instead - Elysium, during which I mostly slept. I couldn't summon tremendous enthusiasm for the Hugo evening anyway. Some undeniably good works were nominated, and I didn't sense any great outpouring of anger after the results. I'd have liked 2312 to do well, certainly, but John Scalzi has been such a force for good in the field, taking a genuinely heroic stand, that I doubt anyone would have much begrudged his win for Redshirts, quite aside from the fact that it had many admirers. The fact is, though, that I didn't even vote. I just couldn't summon up the enthusiasm or the energy, in a professionally difficult year in which I'd read almost nothing eligible and in which the one book I did rate highly - 2312 - was to some extent likely to overshadow my own eligible novel, Blue Remembered Earth. (Stan's is the better novel, though - go and read it). I needn't have worried, though. When the full Hugo results were made available, nothing of mine had come to close to being nominated, let alone winning. Normally there's a work or two of mine somewhere down below the cutoff, which is enough to provide some crumb of consolation, but this year there was nothing. I suppose I shouldn't be too surprised - I've made plain my thoughts on SF's year-long awards circus - but it was sobering all the same, as if my entire SF career was happening in some parallel world entirely removed from the Hugos. To be fair, I have had one Hugo nomination, for Troika back in 2011, for which I was genuinely grateful, and which is one more Nebula nomination than I've managed to notch up in 23 years of professional publishing. All of which probably sounds bitter, but actually I'm more bemused than disappointed. I do well enough commercially, and people whose opinions matter to me occasionally say nice things about my fiction. My short fiction is widely reprinted and anthologised. But the field has two conspicuous badges of merit, the Hugos and the Nebulas, and judging by those I'm just barely on the map.

Rather than end on a downbeat note, though, I'll reiterate that I enjoyed the convention very much. I appreciated the work that went in behind the scenes, and I saw a lot of people having a great time. I was personally disappointed that my friends from Helsinki did not succeed in winning their bid for 2015, but - hey - London is next. And awards or otherwise, I hope to be there.

Thursday 5 September 2013

Chiefly nocturnal

Eagle Owl caption, Field museum of natural history, Chicago. I have no idea why the upright image insists on displaying like this, but I'll fix it when I return to the UK. Among many things about the wonderful Field museum, I loved that they had made no attempt to update the dated diction and tone of their older captions. I wish more museums kept faith with the past in this fashion, rather than constantly chasing an ever decreasing attention span. "This results in the discomfiture of the owl", indeed.

Friday 16 August 2013

ISS

Unless you're on it, the International Space Station is a long way away - 400 or more km, even if it's flying right overhead - but on the other hand, it's huge. Modern digital cameras and lenses can do surprisingly well at capturing images of such a large and distant object, so - having been impressed by some of the pictures I've seen on the web - I thought I'd have a go myself.

This is my first proper effort -I tried a couple of nights ago with my camera on automatic mode, but the battery was low and in the low light conditions I struggled with finding the focus at infinity (my camera has a continuous focussing dial, so there's no handy end-stop). Tonight I set the ISO to 800 and the shutter speed to 1/500th, and focused on the Moon and a couple of stars beforehand. My cameras is a Lumix FZ50 with a 1.5 teleconverter on top of the built-in 420mm lens. The sky was clear except for some cirrus and the pass was a bright one. I balanced my camera on a wheelie-bin, as I've seen mentioned elsewhere - good tip. A tripod is not much use as you can't track fast enough to keep on the station.

What do you reckon? It looks like I've resolved something more than a smudge, but I admit it's not very scientific. Next time, I'll take a sequence of exposures at the same angle and see if there's any consistency between the images.

Enlargement:

This is my first proper effort -I tried a couple of nights ago with my camera on automatic mode, but the battery was low and in the low light conditions I struggled with finding the focus at infinity (my camera has a continuous focussing dial, so there's no handy end-stop). Tonight I set the ISO to 800 and the shutter speed to 1/500th, and focused on the Moon and a couple of stars beforehand. My cameras is a Lumix FZ50 with a 1.5 teleconverter on top of the built-in 420mm lens. The sky was clear except for some cirrus and the pass was a bright one. I balanced my camera on a wheelie-bin, as I've seen mentioned elsewhere - good tip. A tripod is not much use as you can't track fast enough to keep on the station.

What do you reckon? It looks like I've resolved something more than a smudge, but I admit it's not very scientific. Next time, I'll take a sequence of exposures at the same angle and see if there's any consistency between the images.

Enlargement:

Tuesday 13 August 2013

Grrrr

My story "At Budokan", which originally appeared in Jetse de Vries's Shine anthology, is now available to read for free in Lightspeed magazine:

http://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/fiction/at-budokan/

Monday 12 August 2013

Mural and Year's Best

I was delighted to hear from Dakota Freeman, a physics and mathematics undergraduate at MIT. Dakota tells me that they're allowed to paint more or less whatever they like on the dorm walls, which strikes me as a great concept. For Dakota's dorm the inspiration came from the cover of my collection Deep Navigation. Says Dakota: "I particularly enjoyed "Fresco" and "Tiger, Burning", though my favorite story of yours is definitely "House of Suns."

A person of taste and refinement, I think we can agree.

Here's the magnificent result:

Thanks, Dakota - I'm honored.

In other news, I'm as thrilled as ever to be included in the latest edition of Gardner Dozois' Year's Best Science Fiction, in this case, amazingly enough, the thirtieth annual selection. This year Gardner has kindly chosen my story The Water Thief, which originally appeared in Arc magazine at the start of 2012.

You might think I'm terribly blase about this sort of thing but it couldn't be further from the truth. I still get an immense kick out of being picked for inclusion in the Year's Best. Back when I started reading Interzone, in 1985, the SF field was undergoing one of its periodic bursts of reinvention - in this case, the emergence of a whole new slew of writers loosely organised into the "cyberpunk" and "humanist" camps. Interzone published some of these writers, but equally there were a large number that one could only read about in the reviews and commentary section. When I got hold of my first copy of one of Gardner's anthologies, it felt like gold dust. That was 1987, and the confusingly retitled British edition offered no hint that this series had already been running for some while. Quite apart from the contents of the anthology - which contained, among other things, Bruce Sterling's "The Beautiful and the Sublime" - the volume also had a lengthy overview of the preceeding year in SF, as well as a huge selection of "honorable mentions" at the back of the book. In a way, these lists of titles were at least as fascinating as the anthologised pieces themselves because one could imagine the stories that fitted the titles. Some writers seemed to have a gift for brilliant titles. I remember thinking that this Lucius Sheperd dude sure came up with some good ones.

Years later, when I'd started selling short fiction, I would anxiously scan the "honorable mentions" in the hope of, well, an honorable mention. I remember being gutted when a story I regarded as my strongest to date didn't merit so much as a nod, let alone inclusion in the book. That was one of those moments when I almost considered giving up. Yet, within a year or two of that, I found myself on Gardner's radar and before very long, he had picked a story of mine for inclusion. That was an amazing feeling. I was on a high for months, counting down the days until the book appeared. It's been a kick every time since - and just as much as a downer when I haven't managed to get a story into the book. In other words, it still matters to me. There are other "Year's Best" editions out there, all edited by people of sound judgement (some are even friends of mine) but Gardner's will always be "the big one" as far as I'm concerned.

So here we are, twenty five-odd years later, and it's a blast to be included.

Amazon.com link:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Years-Best-Science-Fiction/dp/1250029139/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1376300246&sr=8-1&keywords=dozois+thirtieth

Amazon.co.uk:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Mammoth-Book-Best-Books/dp/1472106016/ref=sr_1_9?ie=UTF8&qid=1376300312&sr=8-9&keywords=best+new+science+fiction

A person of taste and refinement, I think we can agree.

Here's the magnificent result:

Thanks, Dakota - I'm honored.

In other news, I'm as thrilled as ever to be included in the latest edition of Gardner Dozois' Year's Best Science Fiction, in this case, amazingly enough, the thirtieth annual selection. This year Gardner has kindly chosen my story The Water Thief, which originally appeared in Arc magazine at the start of 2012.

You might think I'm terribly blase about this sort of thing but it couldn't be further from the truth. I still get an immense kick out of being picked for inclusion in the Year's Best. Back when I started reading Interzone, in 1985, the SF field was undergoing one of its periodic bursts of reinvention - in this case, the emergence of a whole new slew of writers loosely organised into the "cyberpunk" and "humanist" camps. Interzone published some of these writers, but equally there were a large number that one could only read about in the reviews and commentary section. When I got hold of my first copy of one of Gardner's anthologies, it felt like gold dust. That was 1987, and the confusingly retitled British edition offered no hint that this series had already been running for some while. Quite apart from the contents of the anthology - which contained, among other things, Bruce Sterling's "The Beautiful and the Sublime" - the volume also had a lengthy overview of the preceeding year in SF, as well as a huge selection of "honorable mentions" at the back of the book. In a way, these lists of titles were at least as fascinating as the anthologised pieces themselves because one could imagine the stories that fitted the titles. Some writers seemed to have a gift for brilliant titles. I remember thinking that this Lucius Sheperd dude sure came up with some good ones.

Years later, when I'd started selling short fiction, I would anxiously scan the "honorable mentions" in the hope of, well, an honorable mention. I remember being gutted when a story I regarded as my strongest to date didn't merit so much as a nod, let alone inclusion in the book. That was one of those moments when I almost considered giving up. Yet, within a year or two of that, I found myself on Gardner's radar and before very long, he had picked a story of mine for inclusion. That was an amazing feeling. I was on a high for months, counting down the days until the book appeared. It's been a kick every time since - and just as much as a downer when I haven't managed to get a story into the book. In other words, it still matters to me. There are other "Year's Best" editions out there, all edited by people of sound judgement (some are even friends of mine) but Gardner's will always be "the big one" as far as I'm concerned.

So here we are, twenty five-odd years later, and it's a blast to be included.

Amazon.com link:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Years-Best-Science-Fiction/dp/1250029139/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1376300246&sr=8-1&keywords=dozois+thirtieth

Amazon.co.uk:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Mammoth-Book-Best-Books/dp/1472106016/ref=sr_1_9?ie=UTF8&qid=1376300312&sr=8-9&keywords=best+new+science+fiction

Thursday 18 July 2013

From sketch to cover

Everyone loved the hardback cover of Blue Remembered Earth by Dominic Harman (me especially), but for the smaller format required for the paperback edition, it was felt that a significant redesign was needed, together with a visual element that emphasized the space-based action of much of the book. In other words, another spaceship.

There is no one spaceship that dominates the action in BRE - I actually tried to make the various craft more like routine vehicles than major characters in their own right - but it was clear that the ship "Winter Queen", which figures in the later action, might not be a bad choice. It also serves as a generic template for the basic look of some of the other vehicles mentioned in the book, such as the Maersk Intersolar liner and the Kinyeti - hopefully conveying a sense that these technologies are only a little more advanced than what we have now.

To give the artist (I think it was also Dominic) something to go on, I provided this extremely rough and ready sketch:

It's very interesting to compare it to the final cover - note the "details don't matter". I liked the final interpretation very much, although I've still a soft spot for the original cover, with its lovely hues and evocation of Earth.

Friday 5 July 2013

Eagles High

Eagle, the hugely popular children's comic, casts a very long shadow. In its original incarnation it ran from 1950 to 1969. Its golden age, however, was even shorter than that, for by the mid sixties the comic (which was always aimed squarely at boys) was struggling to find its place in a world of television, pop music and a new era of global sport.

Yet the reach of the magazine was huge, and there must be countless children who came to a knowledge of Eagle not through the comic itself, but through the durable hardback annuals, which would have belonged to our parents and relatives a decade or more earlier.

Such was the case for me, for my father's copy of Eagle Annual 3 soon passed into my possession:

The annual was published in 1953, when my father would have been ten. By the time it entered my consciousness, in the early seventies, it would have been the better part of twenty years old. Of course, it had something of an old fashioned feel to it but it was also a very attractive and colourful package, and I found much to enjoy in it. Not least, of course, the colour spread containing the adventure of Dan Dare and the Double-Headed Eagle:

This would have been my first encounter with Dare and of course I came to it without any establishing context, knowing nothing of the characters or their world. I remember looking at the pictures with some interest, long before I was able to work my way through the story and grasp the "plot", such as it is. But it has stayed with me ever since.

Eagle, though, was not just about the science fiction exploits of Dan Dare although he may well have been the comic's most iconic creation. The comic set out to be educational as well as entertaining, and it was stuffed with factual articles, as well as stories and comic strips documenting historical events. The comic took an optimistic view of technological and scientific progress - this, after all, was the time of the Festival of Britain, a period when the memory of the war was beginning to fade and a newly invigorated Britain was still a world class player in engineering, ranging from supersonic aircraft to record-breaking motor cars. Eagle championed all this and more. Known for its staggeringly detailed cutaway drawings of then contemporary technological marvels, Eagle had tapped into an audience warmly appreciative of such matters. A few years ago I was delighted to pick up this Eagle "spinoff":

Times were moving on, though, and there's no doubt that the appetite for such wholesome educational material could not be sustained. Eagle was gone by time of the Apollo landing, and yet magazines of the same general "improving" type must have taken a long time to fade away completely. Four years after the demise of Eagle, for instance, this was one of my Christmas presents in 1973:

Now, I have no idea whether or not "Tell Me Why" had an existence independent from this annual, but between the covers it's really just a slightly updated variation on the Eagle theme. There are factual articles - the book opens with a chapter on the wonders of modern Japan - but also cutaway drawings, historical comic strips and so on. It's a very similar formula.

For better or for worse, I don't think it's possible to understate the degree to which these annuals colonised my imagination. Here's an example: I know the story of Earnest Shackleton well enough as an adult - I have read about it, and seen television documentaries. But my sense of the internal narrative of the story is entirely predicated on this monochrome comic strip from the Tell Me Why annual:

It's actually quite a fantastically good piece of history as entertainment, and that choice of blue as the sole tinting is suitably chilly. Elsewhere in the annual, there are similar stories and articles which still form the bedrock for my understanding of the relevant subject. (There's one on early lighthouses, for instance, which will always flash through my mind whenever someone mentions lighthouses, and another on the sinking of a Japanese aircraft carrier).

Yes, there was something very dated, very paternal, in these magazines - especially in their assumed choices of content, for the middle class male readership they undoubtedly had in mind. But I cannot deny that they have played a part in shaping my view of things, and stimulating my interest in what, for want of a better word, one might call "progress". I accept their deficiencies but at the same time I am quietly pleased to have been born in the shadow of Eagle.

Yet the reach of the magazine was huge, and there must be countless children who came to a knowledge of Eagle not through the comic itself, but through the durable hardback annuals, which would have belonged to our parents and relatives a decade or more earlier.

Such was the case for me, for my father's copy of Eagle Annual 3 soon passed into my possession:

The annual was published in 1953, when my father would have been ten. By the time it entered my consciousness, in the early seventies, it would have been the better part of twenty years old. Of course, it had something of an old fashioned feel to it but it was also a very attractive and colourful package, and I found much to enjoy in it. Not least, of course, the colour spread containing the adventure of Dan Dare and the Double-Headed Eagle:

This would have been my first encounter with Dare and of course I came to it without any establishing context, knowing nothing of the characters or their world. I remember looking at the pictures with some interest, long before I was able to work my way through the story and grasp the "plot", such as it is. But it has stayed with me ever since.

Eagle, though, was not just about the science fiction exploits of Dan Dare although he may well have been the comic's most iconic creation. The comic set out to be educational as well as entertaining, and it was stuffed with factual articles, as well as stories and comic strips documenting historical events. The comic took an optimistic view of technological and scientific progress - this, after all, was the time of the Festival of Britain, a period when the memory of the war was beginning to fade and a newly invigorated Britain was still a world class player in engineering, ranging from supersonic aircraft to record-breaking motor cars. Eagle championed all this and more. Known for its staggeringly detailed cutaway drawings of then contemporary technological marvels, Eagle had tapped into an audience warmly appreciative of such matters. A few years ago I was delighted to pick up this Eagle "spinoff":

Times were moving on, though, and there's no doubt that the appetite for such wholesome educational material could not be sustained. Eagle was gone by time of the Apollo landing, and yet magazines of the same general "improving" type must have taken a long time to fade away completely. Four years after the demise of Eagle, for instance, this was one of my Christmas presents in 1973:

Now, I have no idea whether or not "Tell Me Why" had an existence independent from this annual, but between the covers it's really just a slightly updated variation on the Eagle theme. There are factual articles - the book opens with a chapter on the wonders of modern Japan - but also cutaway drawings, historical comic strips and so on. It's a very similar formula.

For better or for worse, I don't think it's possible to understate the degree to which these annuals colonised my imagination. Here's an example: I know the story of Earnest Shackleton well enough as an adult - I have read about it, and seen television documentaries. But my sense of the internal narrative of the story is entirely predicated on this monochrome comic strip from the Tell Me Why annual:

It's actually quite a fantastically good piece of history as entertainment, and that choice of blue as the sole tinting is suitably chilly. Elsewhere in the annual, there are similar stories and articles which still form the bedrock for my understanding of the relevant subject. (There's one on early lighthouses, for instance, which will always flash through my mind whenever someone mentions lighthouses, and another on the sinking of a Japanese aircraft carrier).

Yes, there was something very dated, very paternal, in these magazines - especially in their assumed choices of content, for the middle class male readership they undoubtedly had in mind. But I cannot deny that they have played a part in shaping my view of things, and stimulating my interest in what, for want of a better word, one might call "progress". I accept their deficiencies but at the same time I am quietly pleased to have been born in the shadow of Eagle.

Wednesday 26 June 2013

The Foss Way

Over at http://www.unlikelyworlds.blogspot.co.uk/ Paul McAuley has been posting some classic 70s paperback SF images, many of which are by the incomparable Chris Foss. These days, it's perhaps hard to grasp the extent to which the spaceship-orientated visual style of Chris Foss was absolutely inseparable from SF, to the extent that many of the other artists of the period were obliged to emulate the Foss look. I adored Foss's work even as I came to the sobering conclusion that most of the images had nothing whatsoever to do with the contents of the book.

This seemed as good a time as anyway to reprint my review of Hardware, which originally appeared in the BSFA's Vector magazine:

"That'll never happen."

These words were delivered by a geography teacher, examining a paperback of Asimov short stories that I'd foolishly allowed to remain visible on my desk. The focus of his scorn was not the contents of the book, of which he remained ignorant, but the cover, a painting of some daunting megastructure rising above an alien moon. Actually, I'd have readily agreed with him that not only would the depicted situation "never happen", but there was a vanishingly small chance of it having much to do with the stories in the book. This, after all, was a Chris Foss cover. Foss covers seldom related to anything.

It didn't matter. I loved Foss and I still do. The colour, the drama, the vast sense of scale and possibility - his pictures have always delighted me. Liberated from the texts themselves, as they are in this massive restrospective edition, it matters even less. Foss has been prolific, so clearly nothing less than a big book will suffice. I haven't counted, but with more than 230 pages, a good number of which are divided into three or four panels, Hardware must contain well over 500 illustrations, all - to my eye - well reproduced on good quality paper. Given the proviso that it's almost all machinery and landscapes, the range is impressive. There are, for instance, fifteen paintings just of submarines. There's a two-page spread devoted solely to paintings of things being grabbed by giant robot claws coming out of the sea. Hundreds and hundreds of spaceships, space stations, bases, asteroids, towering robots, explosions. People crop up here and there, but they're not the reason we come to Foss. His most iconic images are largely devoid of the human element. Personal favorites: the marvellous double-spread picture for "A Torrent of Faces" - Ballardian entropy made manifest, even though it isn't a Ballard book, and the gorgeous single image that was split into three for the Foundation trilogy.

It's such a generous assortment that it seems churlish to quibble. I'd have appreciated an index by book title, and I'd be slightly wary of the date attributions: my edition of Harry Harrison's In Our Hands The Stars, for instance, with its gorgeous cover of a chequerboard spacecraft rising from a night-lit cityscape, dates from 1981, not the 1986 stated here. There's also little about Foss the man: other than a single small photograph from 1977, there's no image of him (and even in the photo, it's not obvious which one is Foss). I'd have appreciated a sense of the artist in his natural habitat. We're assured that Foss is still active, but there's little evidence of that from the images, few of which date from later than the early 90s. Clearly, SF paperback illustration is a very different game than it was in the "golden age" of the seventies, but Foss's work still looks pretty timeless to me. It would be good to see new work, but in the meantime this lavish book is a fitting retrospective.

Thursday 20 June 2013

Denver pissed him off

There's almost certainly a post to be done on the influence of Joe Haldeman's work on my writing (I've been a huge admirer of Haldeman's work since I finally scored a paperback copy of The Forever War, years after reading about it, in those valve-driven days of the early 80s) but for now I was happy to be given the chance to review The Best of Joe Haldeman over at the Los Angeles Review of Books. Some quibbles aside (I'd have liked the book to feel more like an "event") this is a fine way to sample more than forty years of short fiction output by one of the most significant voices to enter the field in the last half century.

You can read the full review here.

Wednesday 12 June 2013

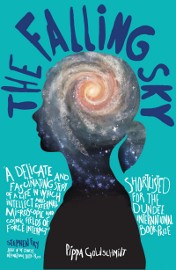

The Falling Sky

Belatedly, my review of Pippa Goldschmidt's excellent novel The Falling Sky appeared on Arcfinity a few weeks ago:

"Pippa Goldschmidt’s The Falling Sky is that rare thing: a literary novel that gets under the hood of science as a social enterprise, done by real and fallible people. It’s an extremely accomplished debut and the best evocation of the actual life of an astronomer I’ve ever read."

You can read the full review here. It's a fantastic book which deserves some attention. As a literary novel about the process of science rather than a piece of genre science fiction, I doubt that it will receive recognition from any of the field's usual awards - although if the Clarke can extend its remit to include genre fantasy, I see no reason why this book could not be shown the same generosity of spirit. Novels about science are rare enough things. In any case it would be encouraging to see it on some mainstream shortlists. Stephen Fry liked it.

Tuesday 11 June 2013

Bookplates and book signing arrangements

I've fallen quite badly behind on sending out bookplates over the last few months, but with my wife's help I've had a bit of a catch up and signed plates should now be on their way out to you. If you've requested bookplates from me ages ago (say, before start of this year) and you're still waiting, feel free to drop me a gentle reminder at the usual address, available on the website:

www.alastairreynolds.com

As a general reminder, I'm happy to sign and personalise bookplates in small quantities at no charge. I normally send out about ten at a time, although I can do more if required. I can either sign my own supply of Orion bookplates (when they're in stock from my publisher), or you can send me some of your own to be signed and returned. I'm also willing to receive, sign and return books, subject to availability and time constraints. As always, drop me a line and we can discuss arrangements. For overseas readers, where providing return postage might be difficult, I generally suggest a charitable donation equal to the incurred postage costs.

www.alastairreynolds.com

As a general reminder, I'm happy to sign and personalise bookplates in small quantities at no charge. I normally send out about ten at a time, although I can do more if required. I can either sign my own supply of Orion bookplates (when they're in stock from my publisher), or you can send me some of your own to be signed and returned. I'm also willing to receive, sign and return books, subject to availability and time constraints. As always, drop me a line and we can discuss arrangements. For overseas readers, where providing return postage might be difficult, I generally suggest a charitable donation equal to the incurred postage costs.

Sunday 9 June 2013

Iain Banks 1954 - 2013

The great Iain Banks has died. We had known this day was coming, of course, after Iain announced his terminal illness a couple of months ago. But it still feels to have happened shockingly, unfairly soon. My thoughts are with Iain's family and friends, and I am very sad that we only got to meet on a handful of occasions.

Here's a snap taken at the last such meeting, late last year, when Iain, Peter Hamilton and I teamed up for a Google hang-out. It was terrific fun, as I think you can tell from the smiles on our faces. Iain was on excellent good form - it was, as ever, a wonderful thing just to be able to hang out with him.

After the event, the three of us went to a nearby pub for a quick pint. Iain had to dash off (Peter and I continued on for a pizza and more beer) but I remember telling Iain that I looked forward to seeing him soon as I wanted to tell him something about Raw Spirit, his 2003 book on whisky. Iain laughed with that particular glint in his eye, but time was tight and the story had to wait. I was confident I'd get a chance one day.

Well, it's not much of a story (the main thing was that it was Iain's book) but here it is anyway. I have had a layman's liking for single malt whiskies for many years without ever going deeper than that simple, uncluttered appreciation. A few months earlier, though, I had picked up a copy of Raw Spirit in the interests of educating myself. On the train up to London I read about the smokey and peatey Laphroaig, which I knew I had tasted and liked, and also Lagavulin, which I did not think I had sampled. That was my mission, then - to try some Lagavulin at the earliest opportunity, and see how it measured up against the Laphroaig.

That night I had attended some literary thing and found myself back in my hotel, alone, at the unreasonably early hour of 10.00 pm. I'm normally a bit hyper after these things so rather than squirrel myself away in the room, I generally prefer to go down to the bar and have a quiet and reflective drink. Suitably emboldened, I stuffed some cash into my pocket and wandered down to the bar. Scanning the whiskies I immediately spotted a bottle of the fabled and as yet unsampled Lagavulin. Just the ticket, I thought. I asked the barman to pour me a single measure, without ice or water. Supposedly you really ought to drink whisky with a small amount of water to activate the aroma (I was told this by a friendly and authoritative Scots barman, during another post-literary drink, but old habits die hard). The London barman poured me my whisky, gave me the glass and told me my single measure would cost in excess of ten pounds.

Yes, that was a shock to me as well - London prices, I suppose - and this was a very swish hotel by my usual standards. But to my dismay I simply did not have enough money on me. The room had been paid for me, so I did not want to get into the complication of charging the drink to my account, and then having to sort that out in the morning. Instead I rather lamely apologised and said I would need to return to my room to get more money, which might take several minutes.

The barman, though, waved aside my embarrasment, took the money I had on me, and told me to enjoy my Lagavulin. Which I did, adding it to my mental register of sampled whiskies, and deciding that it compared well against the Laphroaig. Just the one measure, though. I suppose, in the back of my mind, I might have been half anticipating another, if the Lagavulin had cost about half what it did.

So there - not, as I said, very much of a story, but I think Iain would have been tickled - it was his book, after all, that had brought me to this bar - and at the very least I'd have enjoyed being gently steered to some other discovery.

I did not know Iain terribly well - we had met on, I think, three occasions - but I liked him tremendously and found in his enthusiasms exactly the person you might hope had written all those dense and imaginative novels. If you felt that you knew Iain through his work, then - on my admittedly limited experience of the man - you probably did.

And now I'm off to have a look through my whiskies, because I fancy a dram.

[Update - it was a glass of Laphroaig, because that was all I had in. But very nice all the same.]

Here's a snap taken at the last such meeting, late last year, when Iain, Peter Hamilton and I teamed up for a Google hang-out. It was terrific fun, as I think you can tell from the smiles on our faces. Iain was on excellent good form - it was, as ever, a wonderful thing just to be able to hang out with him.

After the event, the three of us went to a nearby pub for a quick pint. Iain had to dash off (Peter and I continued on for a pizza and more beer) but I remember telling Iain that I looked forward to seeing him soon as I wanted to tell him something about Raw Spirit, his 2003 book on whisky. Iain laughed with that particular glint in his eye, but time was tight and the story had to wait. I was confident I'd get a chance one day.

Well, it's not much of a story (the main thing was that it was Iain's book) but here it is anyway. I have had a layman's liking for single malt whiskies for many years without ever going deeper than that simple, uncluttered appreciation. A few months earlier, though, I had picked up a copy of Raw Spirit in the interests of educating myself. On the train up to London I read about the smokey and peatey Laphroaig, which I knew I had tasted and liked, and also Lagavulin, which I did not think I had sampled. That was my mission, then - to try some Lagavulin at the earliest opportunity, and see how it measured up against the Laphroaig.

That night I had attended some literary thing and found myself back in my hotel, alone, at the unreasonably early hour of 10.00 pm. I'm normally a bit hyper after these things so rather than squirrel myself away in the room, I generally prefer to go down to the bar and have a quiet and reflective drink. Suitably emboldened, I stuffed some cash into my pocket and wandered down to the bar. Scanning the whiskies I immediately spotted a bottle of the fabled and as yet unsampled Lagavulin. Just the ticket, I thought. I asked the barman to pour me a single measure, without ice or water. Supposedly you really ought to drink whisky with a small amount of water to activate the aroma (I was told this by a friendly and authoritative Scots barman, during another post-literary drink, but old habits die hard). The London barman poured me my whisky, gave me the glass and told me my single measure would cost in excess of ten pounds.

Yes, that was a shock to me as well - London prices, I suppose - and this was a very swish hotel by my usual standards. But to my dismay I simply did not have enough money on me. The room had been paid for me, so I did not want to get into the complication of charging the drink to my account, and then having to sort that out in the morning. Instead I rather lamely apologised and said I would need to return to my room to get more money, which might take several minutes.

The barman, though, waved aside my embarrasment, took the money I had on me, and told me to enjoy my Lagavulin. Which I did, adding it to my mental register of sampled whiskies, and deciding that it compared well against the Laphroaig. Just the one measure, though. I suppose, in the back of my mind, I might have been half anticipating another, if the Lagavulin had cost about half what it did.

So there - not, as I said, very much of a story, but I think Iain would have been tickled - it was his book, after all, that had brought me to this bar - and at the very least I'd have enjoyed being gently steered to some other discovery.

I did not know Iain terribly well - we had met on, I think, three occasions - but I liked him tremendously and found in his enthusiasms exactly the person you might hope had written all those dense and imaginative novels. If you felt that you knew Iain through his work, then - on my admittedly limited experience of the man - you probably did.

And now I'm off to have a look through my whiskies, because I fancy a dram.

[Update - it was a glass of Laphroaig, because that was all I had in. But very nice all the same.]

Wednesday 5 June 2013

Doctor Who events (again)

Here's an updated schedule for the Doctor Who events:

Thurday 6th June 6 - 7pm - Forbidden Planet Bristol (Clifton Heights, Triangle West, Bristol BS8 1EJ)

Friday 7th June 6 - 7pm - Forbidden Planet London (179 Shaftesbury Ave, London WC2H 8JR)

Wednesday 12th June - 7pm - Waterstones Cardiff (2A The Hayes, Cardiff CF10 1W). This is a ticketed event - details here.

Thursday 20th June 6.30pm - Forest Bookshop, Coleford, Forest of Dean (8 St John's St, Coleford, Gloucestershire GL16 8AR)

Tuesday 2nd July 8 - 9.30 pm - Toppings Bookshop Bath (The Paragon Bath, Somerset BA1 5LS). This is a ticketed event - details here.

Please note that the Toppings event is in July, not June - I've seen a couple of mistaken listings for that one.

Tuesday 4 June 2013

Harvest of Time - what's it all about, then?

The official publication day for my Doctor Who novel is the 6th of June, but (as tends to happen) I'm hearing reports that copies of the book are already in the wild. I am tremendously excited about it all and looking forward to the signing and reading events to follow in the coming weeks.

That said, I'm well aware that for many of my readers, Doctor Who is going to be a bit of a blank. It is a huge cultural property in the UK, but much less so beyond our shores. It can be intimidating, coming into the continuity of a long-running imaginative universe, so I can imagine some readers might feel justifiable hesitation in picking up the book. This is a series that's been running, on and off, for fifty years - so isn't the backstory hugely complicated and bewildering, something for insiders only?

Obviously, I hope not. And I hope that if you like my other stuff, you might consider giving the Who book a shot. The first thing to say is that my grasp of Doctor Who continuity isn't very detailed - there are huge gaps in my knowledge of the show, and lots of stuff I don't know as well as I should. It doesn't matter, though. At almost any point in its existence, Doctor Who has usually tended to be quite simple in formula, which is one of the reasons that generations of children have been able to jump into the series and feel that it is theirs. It's never been too burdened by its past.

I aspired to write Harvest in such a way that you wouldn't need to know very much about the Doctor Who universe to get on with the book. Whether I've succeeded or not is not for me to say, but not having watched Doctor Who needn't be a reason to give the book a miss. If you have seen the show over the years, you'll hopefully enjoy picking up on the characters and references, but none of that is essential. And as I say, the basic premise is incredibly simple.

The Doctor is a time-travelling humanoid alien, a member of an alien culture known as the Time Lords. The Doctor can regenerate his appearance - my Doctor, played by Jon Pertwee, was the third actor to play the role on television. For various reasons, Pertwee's Doctor spent much of his time confined to Earth in the twentieth century. There's a particular flavour to these Earthbound stories, all of which aired in the early nineteen seventies, and for me they are very much a defining element in my relationship with the series. The Doctor is attached to the British wing of UNIT, a military branch set up to deal with the routine invasion of the planet by various alien factions. The UNIT stories mostly take place in the UK, with a small surrounding cast of regulars. Jo Grant was the Doctor's assistant at the time, a civilian laison to UNIT. Jo answered to the Brigadier, head of the British wing of the organisation. The Doctor and the Brig eventually became friends, but were also at constant loggerheads over the best way to deal with whatever alien invasion was presently on the agenda. Supporting the Doctor, Jo and the Brig were two more UNIT regulars, the soldiers Benton and Yates. And that was your entire regular cast of good guys.

Adding a strong thematic element to this run of Pertwee stories was the introduction of a recurring adversary, in the form of the Master. The Master was also a Time Lord - but a distinctly antisocial one. Like the Doctor, he had rebelled and stolen a shape-changing time machine (Tardis) of his own. They had much in common, and often found themselves "teaming up" to solve a particular crisis, usually of the Master's making. But they were also mortal enemies and the Master was only ever waiting for a chance to kill the Doctor, as he attempted to do so on many occasions. Generally speaking, if some aliens were up to no good, the Master would usually turn out to be involved in the plot on some level. If the Doctor was Holmes, the Master was his Moriarty. A genius with an intellect beyond even that of the Doctor, the Master's downfall was generally caused by his arrogance and conceit.

Like the Doctor, the Master also had the capacity to regenerate. During the Pertwee era he was played to terrific effect by Roger Delgado. Sadly, Delgado was killed in an accident during the actual run of Pertwee stories, meaning that his version of the Master never got the big send-off that he deserved. It would be some years before the Master returned to Doctor Who, but the character remains an important element of the mythos. For me, the Master is the best fictional villain of all time and was at least as strong a motivator for me choosing the Pertwee era as the other characters.

That's really all you need to know. The plot of Harvest of Time depends on some alien villains that are entirely my own invention, and the backstory that I invent in regard to these villains, the Time Lords, the Master and so on, is also unique to the book. At 100,000 words it's about half the length of one of my usual novels, but there's a lot in it - stuff set on Earth, stuff set in the far future - time travel, alien technology, dangerous super-weapons and so on. If you do try it, I hope you enjoy Harvest of Time. If you don't give it a go, there won't be a long to wait until my next normal novel.

Cheers!

That said, I'm well aware that for many of my readers, Doctor Who is going to be a bit of a blank. It is a huge cultural property in the UK, but much less so beyond our shores. It can be intimidating, coming into the continuity of a long-running imaginative universe, so I can imagine some readers might feel justifiable hesitation in picking up the book. This is a series that's been running, on and off, for fifty years - so isn't the backstory hugely complicated and bewildering, something for insiders only?

Obviously, I hope not. And I hope that if you like my other stuff, you might consider giving the Who book a shot. The first thing to say is that my grasp of Doctor Who continuity isn't very detailed - there are huge gaps in my knowledge of the show, and lots of stuff I don't know as well as I should. It doesn't matter, though. At almost any point in its existence, Doctor Who has usually tended to be quite simple in formula, which is one of the reasons that generations of children have been able to jump into the series and feel that it is theirs. It's never been too burdened by its past.

I aspired to write Harvest in such a way that you wouldn't need to know very much about the Doctor Who universe to get on with the book. Whether I've succeeded or not is not for me to say, but not having watched Doctor Who needn't be a reason to give the book a miss. If you have seen the show over the years, you'll hopefully enjoy picking up on the characters and references, but none of that is essential. And as I say, the basic premise is incredibly simple.

The Doctor is a time-travelling humanoid alien, a member of an alien culture known as the Time Lords. The Doctor can regenerate his appearance - my Doctor, played by Jon Pertwee, was the third actor to play the role on television. For various reasons, Pertwee's Doctor spent much of his time confined to Earth in the twentieth century. There's a particular flavour to these Earthbound stories, all of which aired in the early nineteen seventies, and for me they are very much a defining element in my relationship with the series. The Doctor is attached to the British wing of UNIT, a military branch set up to deal with the routine invasion of the planet by various alien factions. The UNIT stories mostly take place in the UK, with a small surrounding cast of regulars. Jo Grant was the Doctor's assistant at the time, a civilian laison to UNIT. Jo answered to the Brigadier, head of the British wing of the organisation. The Doctor and the Brig eventually became friends, but were also at constant loggerheads over the best way to deal with whatever alien invasion was presently on the agenda. Supporting the Doctor, Jo and the Brig were two more UNIT regulars, the soldiers Benton and Yates. And that was your entire regular cast of good guys.

Adding a strong thematic element to this run of Pertwee stories was the introduction of a recurring adversary, in the form of the Master. The Master was also a Time Lord - but a distinctly antisocial one. Like the Doctor, he had rebelled and stolen a shape-changing time machine (Tardis) of his own. They had much in common, and often found themselves "teaming up" to solve a particular crisis, usually of the Master's making. But they were also mortal enemies and the Master was only ever waiting for a chance to kill the Doctor, as he attempted to do so on many occasions. Generally speaking, if some aliens were up to no good, the Master would usually turn out to be involved in the plot on some level. If the Doctor was Holmes, the Master was his Moriarty. A genius with an intellect beyond even that of the Doctor, the Master's downfall was generally caused by his arrogance and conceit.

Like the Doctor, the Master also had the capacity to regenerate. During the Pertwee era he was played to terrific effect by Roger Delgado. Sadly, Delgado was killed in an accident during the actual run of Pertwee stories, meaning that his version of the Master never got the big send-off that he deserved. It would be some years before the Master returned to Doctor Who, but the character remains an important element of the mythos. For me, the Master is the best fictional villain of all time and was at least as strong a motivator for me choosing the Pertwee era as the other characters.

That's really all you need to know. The plot of Harvest of Time depends on some alien villains that are entirely my own invention, and the backstory that I invent in regard to these villains, the Time Lords, the Master and so on, is also unique to the book. At 100,000 words it's about half the length of one of my usual novels, but there's a lot in it - stuff set on Earth, stuff set in the far future - time travel, alien technology, dangerous super-weapons and so on. If you do try it, I hope you enjoy Harvest of Time. If you don't give it a go, there won't be a long to wait until my next normal novel.

Cheers!

Monday 3 June 2013

Strange Horizons fund raising picture

Strange Horizons is one of the best places on the net for intelligent and informed discussion about the literatures of the fantastic, and we're lucky to have it. Once a year the magazine runs a fund drive and on the last couple of occasions, I've offered an original painting as one of the potential prizes.

I'm pleased to say that Duncan Lawie was the winner of the painting this year, and this is the picture I did. The artwork was produced on canvas board using a background of airbrushed acrylic ink, with a foreground of painted acrylics. I had a bit of fun using metallic silver for the highlights on the spaceship and asteroids, giving the finished piece a distinctive shimmer.

What's going on? No idea, but it looks to me as if the ship has suffered some sort of explosion and that the nearer of the two asteroids is in the process of being mined for replacement raw materials. The picture is now with Duncan.

I'm pleased to say that Duncan Lawie was the winner of the painting this year, and this is the picture I did. The artwork was produced on canvas board using a background of airbrushed acrylic ink, with a foreground of painted acrylics. I had a bit of fun using metallic silver for the highlights on the spaceship and asteroids, giving the finished piece a distinctive shimmer.

What's going on? No idea, but it looks to me as if the ship has suffered some sort of explosion and that the nearer of the two asteroids is in the process of being mined for replacement raw materials. The picture is now with Duncan.

Thursday 30 May 2013

Let's all go to the ISS

During a much needed clear out, I came across this issue of the short-lived British magazine Speed&Power from very early in 1975. As I've mentioned elsewhere, S&P was essentially my gateway into SF since they reprinted many short stories by Arthur C Clarke and (later) Isaac Asimov. (Note, incidentally, the "Reynolds" pencilled into the upper right corner of the magazine, by the newsagent in Barry who kept my copy aside each week).

What caught my eye this time was a neat little article on the construction and operation of America's future space station. The article would have been written in 1974, seven years before the first flight of the space shuttle, and a decade ahead of Reagan's announcement of the first proposal for the actual station, then called Freedom, in the mid nineteen eighties, and a full quarter of a century ahead of the actual constuction of the station.