I've been head-down writing a new book for most of this year, so updates have been few and far between, especially these last few months. I'm pleased to have delivered the book in question, the direct sequel to Revenger, and hope to share a bit more news about it as we go through the usual editing cycle. The book does have a provisional title, but it won't be Revealer, although you'll see that listed here and there. That was a working-working title which wasn't ever meant to be shared with the world, although I really ought to know by now that these things soon escape into reality.

What can I say about it? Not much. Like Revenger, it's a first person narrative, but the voice this time belongs to Adrana, not Fura, and I think that lends the book a somewhat different feel, as well as giving us a different eye on Fura. I think it fair to say that this book is "dark". My next full-length novel will be a continuation of their story.

I might as well mention a few short story related things while I'm at it, some of which have been touched on in earlier posts.

"Holdfast", my story in Extrasolar (edited by Nick Gevers) has now been published, in a very handsome hardcover edition from PS Publishing:

http://www.pspublishing.co.uk/extrasolar-hardcover-edited-by-nick-gevers-4319-p.asp

"Night Passage", my new story in the Revelation Space universe, appeared in Infinite Stars, edited by Bryan Thomas Schmidt, and I'm pleased to say that it's already been picked up by one of the "Year's Best" anthologies.

https://titanbooks.com/infinite-stars-9264/

"Belladonna Nights", which takes place in the House of Suns universe (but prior to that novel) should appear in Subterranean Press's The Weight of Words before the end of 2017, although I've yet to see a copy:

https://subterraneanpress.com/slider-tabs/at-the-printer/mckean-the-weight-of-words

And that story has also been picked up for one of the Year's Bests, and I'm delighted by that as well.

I also wrote a story, exactly 2001 words long, for a tribute anthology to a certain author born one hundred years ago, but it now looks as if that book will be delayed until next year. More news on that one in due course.

Other than that, the only outstanding story of mine is "Different Seas", which will appear in Twelve Tomorrows, from MIT Press, again in 2018, although as yet I can't find a link to the coming edition.

So what else is new?

First up, the Foruli limited edition of Revelation Space is now out in the world, and, although I say it myself, I think it's an extremely impressive and desirable thing. It probably deserves a blog post all to itself, but for now, you can learn a bit more about it here:

https://foruli.co.uk/editions/revelation-space

(Click on the "images" tab to see a hint of the art prints that come with the signature edition).

It's taken quite a few years to get this thing into existence, but I think the wait has been worth it, and I hope the book does well for Foruli. Obviously, it's not cheap, but that's what "limited edition" means, and I think Reynolds completists, if such beings exist, will definitely want this.

The other thing that those hypothetical completists might want - and again, this merits a post of its own - is the new album by Sound of Ceres, who are Ryan and Karen Hover from Colorado, and who make quite lovely music.

https://soundofceres.bandcamp.com/

Because, other than being very enjoyable in its own right, the record includes an original piece of fiction by me. That's right, a brand new short story, otherwise unavailable. It's not just any old vignette, either. I was sent the lyrics, and some early mixes of the tracks, earlier this year, and I tried to riff off the images and moods therein, creating a short story that has an integral relationship with the sounds on the album. It's a beautiful recording, especially in the vinyl edition, and very much recommended for those who enjoy dreampop, Cocteaus, analog synth sounds and so on. Really rather fantastic.

That's it for now. I have a short story to write next, then a novella, and then back into the world of Revenger. I hope all is well with everyone and wish you a satisfactory end to the year.

Al

Monday, 4 December 2017

Sunday, 12 November 2017

Sherlock Holmes: Indestructible

In 1942 Basil Rathone and Nigel Bruce starred in their third film together, Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror. Set during the second world war, rather than the more usual late Victorian period, this briskly paced film includes a title card which explains that the titular detective is "ageless, invincible and unchanging".

Before we are introduced to any of the characters, the central problem is made clear. A Nazi propaganda station is broadcasting as "The Voice of Terror", crowing over recent military successes and making stark threats about sabotage attacks which have either happened or are just happening as the broadcast takes place. As the radio transmission plays out, we are shown some of these terrible events. In one sequence, for instance, we are informed that "an important diplomat boarded a train at a little station outside Liverpool", followed by shots of the signal levers being worked by seemingly ghostly means, leading to the rails being divided and a catastrophic crash, with the train hurtling off the tracks and down a ravine. Throughout the broadcast the phrase "This is the Voice of Terror" is repeated in ominous fashion.

I couldn't help wondering if this fictionalised version of Nazi propaganda broadcasts might have been the direct inspiration for the alien threats at the start of each episode (or sometimes after a lengthy "cold open") of Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons - see here, for instance, at around 6.15 minutes:

Tonally, they are very similar, and of course the Mysterons often went about their acts of alien sabotage by ghostly means, making levers work by themselves, etc. There is also the matter of Captain Scarlet's Mysteron-induced invulnerability, making him ageless, invincible and unchanging. Elementary, one might almost say.

Before we are introduced to any of the characters, the central problem is made clear. A Nazi propaganda station is broadcasting as "The Voice of Terror", crowing over recent military successes and making stark threats about sabotage attacks which have either happened or are just happening as the broadcast takes place. As the radio transmission plays out, we are shown some of these terrible events. In one sequence, for instance, we are informed that "an important diplomat boarded a train at a little station outside Liverpool", followed by shots of the signal levers being worked by seemingly ghostly means, leading to the rails being divided and a catastrophic crash, with the train hurtling off the tracks and down a ravine. Throughout the broadcast the phrase "This is the Voice of Terror" is repeated in ominous fashion.

I couldn't help wondering if this fictionalised version of Nazi propaganda broadcasts might have been the direct inspiration for the alien threats at the start of each episode (or sometimes after a lengthy "cold open") of Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons - see here, for instance, at around 6.15 minutes:

Tonally, they are very similar, and of course the Mysterons often went about their acts of alien sabotage by ghostly means, making levers work by themselves, etc. There is also the matter of Captain Scarlet's Mysteron-induced invulnerability, making him ageless, invincible and unchanging. Elementary, one might almost say.

Sunday, 29 October 2017

Gestation Time

In the previous post I mentioned that my new story "Night Passage" - just out in the Infinite Stars anthology - was one I was glad to see in print because it had taken about five years to finish. I thought that was approximately the case, but when I checked my hard drive I saw that I opened a file on that story at the end of November 2009, so the better part of eight years ago. That wasn't an attempt at the story itself, but as per my usual working method, a set of notes toward a possible idea. I rarely start work on a story cold, but instead prefer to brainstorm a series of rambling, sometimes contradictory thoughts, out of which I hope something coherent may emerge. This process can take anything from a morning to several days or weeks, but I never start a story in the first fire of inspiration.

Over the next five or six years I made a number of attempts to get to grips with the story, but each abandoned draft took the plot further from the initial concept, and with (I think) steadily dwindling focus. Prompted by the need to write a fresh story for this anthology, though, I discarded these efforts, opened a fresh file, and returned to the original notes from 2009. Other than the addition of a framing device which was not present in the notes, the finished story conforms very closely to those initial ideas.

Time and again in my writing, I've had an idea for a story, but in the writing itself, found myself moving further and further away from the core, until some realisation arrives and I discard these over-wrought, over-complicated, over-embroidered drafts and pare things back down to the initial impulse. I'm either incapable of learning from experience, or the process of drift and return is a necessary one.

Over the next five or six years I made a number of attempts to get to grips with the story, but each abandoned draft took the plot further from the initial concept, and with (I think) steadily dwindling focus. Prompted by the need to write a fresh story for this anthology, though, I discarded these efforts, opened a fresh file, and returned to the original notes from 2009. Other than the addition of a framing device which was not present in the notes, the finished story conforms very closely to those initial ideas.

Time and again in my writing, I've had an idea for a story, but in the writing itself, found myself moving further and further away from the core, until some realisation arrives and I discard these over-wrought, over-complicated, over-embroidered drafts and pare things back down to the initial impulse. I'm either incapable of learning from experience, or the process of drift and return is a necessary one.

Saturday, 28 October 2017

Infinite Stars

Out now is Infinite Stars, a mixed reprint/original anthology edited by Bryan Thomas Schmidt:

The book contains an entirely new 16,000 word story of mine, entitled "Night Passage", which happens to be set in the Revelation Space universe. The story revolves around the discovery of the first "Shroud", a class of alien artefact which goes on to play a significant role in the future history.

My story took about five years to write, so I am very pleased to finally see it both completed and in print.

Here are the stories:

“Renegat” (Ender) by Orson Scott Card

“The Waters Of Kanly” (Dune) by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson

“The Good Shepherd” (Legion of the Damned) by William C. Dietz

“The Game Of Rat and Dragon” by Cordwainer Smith 1956 Hugo Best Story, 1955 Galaxy SF, October

“The Borders of Infinity” (Vorkosigan) by Lois McMaster Bujold

“All In A Day’s Work” (Vatta’s War) by Elizabeth Moon

“Last Day Of Training” (Lightship Chronicles) by Dave Bara

“The Wages of Honor” (Skolian Empire) by Catherine Asaro

“Binti” by Nnedi Okorafor TOR.COM, 2015; 2016 Nebula/Hugo/BFA Best Novella

“Reflex” (CoDominium) by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle

“How To Be A Barbarian in the Late 25th Century” (Theirs Not To Reason Why) by Jean Johnson

“Stark and the Star Kings” (Eric John Stark) by Leigh Brackett and Edmond Hamilton

“Imperium Imposter” (Imperium) by Jody Lynn Nye

“Region Five” (Red Series) by Linda Nagata

“Night Passage” (Revelation Space) by Alastair Reynolds

“Duel on Syrtis” by Poul Anderson

“Twilight World” (StarBridge) by A.C. Crispin

“Twenty Excellent Reasons” (The Astral Saga) by Bennett R. Coles

“The Ship Who Sang” by Anne McCaffrey

“Taste of Ashes” (Caine Riardon) by Charles E. Gannon

“The Iron Star” by Robert Silverberg

“Cadet Cruise” (Lt. Leary) by David Drake

“Shore Patrol” (Lost Fleet) by Jack Campbell

“Our Sacred Honor” (Honorverse) by David Weber

And here is a link to the editor's website, where there are a number of purchasing options:

http://bryanthomasschmidt.net/writings/anthologies-edited/infinite-stars-the-definitive-anthology-of-space-opera-and-military-sf/

The book contains an entirely new 16,000 word story of mine, entitled "Night Passage", which happens to be set in the Revelation Space universe. The story revolves around the discovery of the first "Shroud", a class of alien artefact which goes on to play a significant role in the future history.

My story took about five years to write, so I am very pleased to finally see it both completed and in print.

Here are the stories:

“Renegat” (Ender) by Orson Scott Card

“The Waters Of Kanly” (Dune) by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson

“The Good Shepherd” (Legion of the Damned) by William C. Dietz

“The Game Of Rat and Dragon” by Cordwainer Smith 1956 Hugo Best Story, 1955 Galaxy SF, October

“The Borders of Infinity” (Vorkosigan) by Lois McMaster Bujold

“All In A Day’s Work” (Vatta’s War) by Elizabeth Moon

“Last Day Of Training” (Lightship Chronicles) by Dave Bara

“The Wages of Honor” (Skolian Empire) by Catherine Asaro

“Binti” by Nnedi Okorafor TOR.COM, 2015; 2016 Nebula/Hugo/BFA Best Novella

“Reflex” (CoDominium) by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle

“How To Be A Barbarian in the Late 25th Century” (Theirs Not To Reason Why) by Jean Johnson

“Stark and the Star Kings” (Eric John Stark) by Leigh Brackett and Edmond Hamilton

“Imperium Imposter” (Imperium) by Jody Lynn Nye

“Region Five” (Red Series) by Linda Nagata

“Night Passage” (Revelation Space) by Alastair Reynolds

“Duel on Syrtis” by Poul Anderson

“Twilight World” (StarBridge) by A.C. Crispin

“Twenty Excellent Reasons” (The Astral Saga) by Bennett R. Coles

“The Ship Who Sang” by Anne McCaffrey

“Taste of Ashes” (Caine Riardon) by Charles E. Gannon

“The Iron Star” by Robert Silverberg

“Cadet Cruise” (Lt. Leary) by David Drake

“Shore Patrol” (Lost Fleet) by Jack Campbell

“Our Sacred Honor” (Honorverse) by David Weber

And here is a link to the editor's website, where there are a number of purchasing options:

http://bryanthomasschmidt.net/writings/anthologies-edited/infinite-stars-the-definitive-anthology-of-space-opera-and-military-sf/

Thursday, 7 September 2017

NCC 1701

Although I wouldn't presume it's of interest to the majority of my readers, I enjoy making models of things. Just as I can't walk past a record shop (and can't go in one without making a purchase) so I'm a sucker for any model shop/hobby store type establishment. Give me a craft knife, a cutting board, some glue and a CD or two to while away the hours and I couldn't be happier. I suppose it goes back to childhood fridays after school, when a trip to Bridgend market would often see me returning home with the treat of an Airfix kit ... usually reduced to a sticky, finger-printed blob by the end of the evening. Yes, we really knew how to live it up in the old days.

During a trip to Manchester about seven years ago, I snuck off for an hour or two and returned to the hotel with a large and expensive box containing a plastic kit of the USS Enterprise.

As I've mentioned before, I have a particular "thing" for the Enterprise. It makes no sense from an astronautics/physics point of view (what the hell are those warp engines doing so far from the nominal center of gravity?) but it sure does look cool, and this lifelong love affair was firmly cemented by about the age of seven, when I had the Aurora kit of the original version of the ship. I loved everything about the original Enterprise and was heartbroken when one of my warp pylons snapped off (it could nae take the strain, clearly). Later I had the Aurora kit of the Klingon cruiser which suffered a similarly terminal neck-break. Clearly I wasn't destined to possess a Star Trek spaceship for any length of time.

Decades later, and that itch hadn't been adequately scratched, as I still felt the need to own an Enterprise. If I was going to have one, I reasoned, it might as well be big ... and the Polar Lights model, shown above, is certainly on the large side, being 35 inches long when assembled. At the time of purchase, the only kit offered was the one for the "refit" version as featured in the films, and truth to tell I still preferred the clean, art-deco lines of the original ship. Still, it was an Enterprise, wasn't it?

Early on in the build, I decided to light the model from inside. This entailed adding a lot of LEDs and black light-masking, with silver foil to help the light bounce around inside.

In the end the model used about 50 LEDS of various colours, none of which can ever be replaced.

I also added some etched details, including tiny crew figures, barely visible through some of the windows:

I worked on the model during odd evenings over the last few years, but it was only this year that progress really came together. Most of the work involved fitting LEDS, and then laboriously ensuring that no light was spilling out where it shouldn't. For instance, here's the saucer section, fixed together but still being tested and light-blocked:

Finally, the various parts of the model were ready to be assembled and painted. One major step is to cover almost every square inch of the thing with decals, simulating the complex patchwork of shades on the film model. Adding these was very long-winded, but an oddly therapeutic and satisfying process. Finally, the decals for the name, registry number, and so on, were added over the top - literally hundreds of these, since every phaser port, photon torpedo launcher, airlock, etc, has a decal.

At last the model was ready for final finishing, and here it is from another couple of angles compared to the shot at the top of the page.

The biggest pay-off, for me, is when the lights are on. Here's a shot of the overall ship, and a close-up of the shuttle bay.

And the upshot of all this work is that I've formed a very strong appreciation for the refit Enterprise ... to the point where I think I now prefer it to the original version. I think it's a truly beautiful and iconic design, one of the great televisual/cinematic starships. Never mind that it makes no sense!

I hope some of you enjoyed this somewhat off-beat interlude.

Sunday, 3 September 2017

Tuesday, 29 August 2017

It's The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)

That's great! It starts with an earthquake,

Birds and snakes, an aeroplane;

Lenny Bruce is not afraid.

Eye of a hurricane, listen to yourself churn.

World serves its own needs, don't mis-serve your own needs.

Speed it up a notch, speed, grunt, no strength.

The ladder starts to clatter with fear of fight, down height.

Wire in a fire, represent the seven games

In a government for hire and a combat site.

Left her, wasn't coming in a hurry

With the furies breathing down your neck.

Team by team reporters baffled, trump, tethered crop.

Look at that low plane! Fine, then.

Uh oh, overflow, population, common group,

But it'll do. Save yourself, serve yourself.

World serves its own needs, listen to your heart bleed.

Tell me with the rapture and the rev-'rent in the right, right.

You vitriolic, patriotic, slam, fight, bright light;

Feeling pretty psyched.

Birds and snakes, an aeroplane;

Lenny Bruce is not afraid.

Eye of a hurricane, listen to yourself churn.

World serves its own needs, don't mis-serve your own needs.

Speed it up a notch, speed, grunt, no strength.

The ladder starts to clatter with fear of fight, down height.

Wire in a fire, represent the seven games

In a government for hire and a combat site.

Left her, wasn't coming in a hurry

With the furies breathing down your neck.

Team by team reporters baffled, trump, tethered crop.

Look at that low plane! Fine, then.

Uh oh, overflow, population, common group,

But it'll do. Save yourself, serve yourself.

World serves its own needs, listen to your heart bleed.

Tell me with the rapture and the rev-'rent in the right, right.

You vitriolic, patriotic, slam, fight, bright light;

Feeling pretty psyched.

Sunday, 20 August 2017

The Weight of Words

Another new story of mine appears in "The Weight of Words", edited by Dave McKean and William Schafer, and published by Subterranean Press.

Quoting from the publisher's description:

The consummate artistry of Dave McKean has permeated popular culture for more than thirty years. His images, at once bizarre, beautiful, and instantly recognizable, have graced an impressive array of books, CDs, graphic novels, and films. In The Weight of Words, ten of our finest contemporary storytellers, among them the artist himself, have created a series of varied, compelling narratives, each inspired by one of McKean’s extraordinary paintings. The result is a unique collaborative effort in which words and pictures enhance and illuminate each other on page after page.

Like the other authors, I was sent a portfolio of Dave McKean's phenomenal and unsettling images to examine and hopefully be inspired by, and one in particular leapt out at me and immediately suggested both a story and a setting. My piece, Belladonna Nights, is set in the same distant future as House of Suns, and also features Campion from that novel. For me it was deeply enjoyable to re-immerse myself in that universe and explore some of the more arcane traditions of the Lines.

Here's a short excerpt:

I had been thinking about Campion long before I caught him leaving the flowers at my door.

It was the custom of Mimosa Line to admit witnesses to our reunions. Across the thousand nights of our celebration a few dozen guests would mingle with us, sharing in the uploading of our consensus memories, the individual experiences gathered during our two-hundred thousand year circuits of the galaxy.

They had arrived from deepest space, their ships sharing the same crowded orbits as our own nine hundred and ninety nine vessels. Some were members of other Lines—there were Jurtinas, Marcellins and Torquatas—while others were representatives of some of the more established planetary and stellar cultures. There were ambassadors of the Centaurs, Redeemers and the Canopus Sodality. There were also Machine People in attendance, ours being one of the few Lines that maintained cordial ties with the robots of the Monoceros Ring.

And there was Campion, sole representative of Gentian Line, one of the oldest in the Commonality. Gentian Line went all the way back to the Golden Hour, back to the first thousand years of the human spacefaring era. Campion was a popular guest, always on someone or other’s arm. It helped that he was naturally at ease among strangers, with a ready smile and an easy, affable manner—full of his own stories, but equally willing to lean back and listen to ours, nodding and laughing in all the right places. He had adopted a slight, unassuming anatomy, with an open, friendly face and a head of tight curls that lent him a guileless, boyish appearance. His clothes and tastes were never ostentatious, and he mingled as effortlessly with the other guests as he did with the members of our Line. He seemed infinitely approachable, ready to talk to anyone.

Except me.

The book (as far as I can tell, only the trade edition has not already sold out) may be ordered from Subterranean Press:

http://subterraneanpress.com/mckean-the-weight-of-words

Or PS Publishing:

http://www.pspublishing.co.uk/the-weight-of-words-preorder-by-dave-mckean-and-william-schafer-eds-4123-p.asp

Quoting from the publisher's description:

The consummate artistry of Dave McKean has permeated popular culture for more than thirty years. His images, at once bizarre, beautiful, and instantly recognizable, have graced an impressive array of books, CDs, graphic novels, and films. In The Weight of Words, ten of our finest contemporary storytellers, among them the artist himself, have created a series of varied, compelling narratives, each inspired by one of McKean’s extraordinary paintings. The result is a unique collaborative effort in which words and pictures enhance and illuminate each other on page after page.

Like the other authors, I was sent a portfolio of Dave McKean's phenomenal and unsettling images to examine and hopefully be inspired by, and one in particular leapt out at me and immediately suggested both a story and a setting. My piece, Belladonna Nights, is set in the same distant future as House of Suns, and also features Campion from that novel. For me it was deeply enjoyable to re-immerse myself in that universe and explore some of the more arcane traditions of the Lines.

Here's a short excerpt:

I had been thinking about Campion long before I caught him leaving the flowers at my door.

It was the custom of Mimosa Line to admit witnesses to our reunions. Across the thousand nights of our celebration a few dozen guests would mingle with us, sharing in the uploading of our consensus memories, the individual experiences gathered during our two-hundred thousand year circuits of the galaxy.

They had arrived from deepest space, their ships sharing the same crowded orbits as our own nine hundred and ninety nine vessels. Some were members of other Lines—there were Jurtinas, Marcellins and Torquatas—while others were representatives of some of the more established planetary and stellar cultures. There were ambassadors of the Centaurs, Redeemers and the Canopus Sodality. There were also Machine People in attendance, ours being one of the few Lines that maintained cordial ties with the robots of the Monoceros Ring.

And there was Campion, sole representative of Gentian Line, one of the oldest in the Commonality. Gentian Line went all the way back to the Golden Hour, back to the first thousand years of the human spacefaring era. Campion was a popular guest, always on someone or other’s arm. It helped that he was naturally at ease among strangers, with a ready smile and an easy, affable manner—full of his own stories, but equally willing to lean back and listen to ours, nodding and laughing in all the right places. He had adopted a slight, unassuming anatomy, with an open, friendly face and a head of tight curls that lent him a guileless, boyish appearance. His clothes and tastes were never ostentatious, and he mingled as effortlessly with the other guests as he did with the members of our Line. He seemed infinitely approachable, ready to talk to anyone.

Except me.

The book (as far as I can tell, only the trade edition has not already sold out) may be ordered from Subterranean Press:

http://subterraneanpress.com/mckean-the-weight-of-words

Or PS Publishing:

http://www.pspublishing.co.uk/the-weight-of-words-preorder-by-dave-mckean-and-william-schafer-eds-4123-p.asp

Thursday, 17 August 2017

Extra, extra

I'm very pleased to have a new short story in this excellent-sounding new anthology featuring a fine line-up of writers, edited by Nick Gevers.

Here's a description of the book:

Among the brilliant visionary scenarios in Extrasolar: military antagonists meet in the atmosphere of a gas giant; gifted children hijack a starship to search out a new home; a superjovian world yields mysterious and much-coveted gemstones; aliens find our solar system disconcertingly paradoxical; a feminist SF writer of the Seventies crafts liberating exoplanetary dreams; the habitats aboard a gargantuan spaceship cater to the needs of truly exotic aliens; and scientists eagerly seeking exoplanets confront a devastating truth. And then there are songs of home and far away and bitter exile; intelligence calling to intelligence across light years and species barriers; utterly immersive dives into perilous planetary atmospheres; brave responses to enigmatic messages from the stars; a machine embracing a Gothic destiny; and a truly different kind of space opera.

And here's the list of stories:

- Holdfast – Alastair Reynolds

- Shadows of Eternity – Gregory Benford

- A Game of Three Generals – Aliette de Bodard

- The Bartered Planet – Paul Di Filippo

- Come Home – Terry Dowling

- The Residue of Fire – Robert Reed

- Thunderstone – Matthew Hughes

- Journey to the Anomaly – Ian Watson

- Canoe -- Nancy Kress

- The Planet Woman By M.V. Crawford – Lavie Tidhar

- Arcturean Nocturne – Jack McDevitt

- Life Signs – Paul McAuley

- The Fall of the House of Kepler – Ian R. MacLeod

- The Tale of the Alcubierre Horse – Kathleen Ann Goonan

The book is available to purchase from PS Publishing. More information here:

http://www.pspublishing.co.uk/extrasolar-hardcover-edited-by-nick-gevers-4319-p.asp?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=ps_publishing_weekly_newsletter&utm_term=2017-08-17

Tuesday, 15 August 2017

Five Medical Memoirs

Recent reading included five autobiographical books with a common background in medicine. I found them all equally compelling and fascinating. Two of the authors are now deceased.

Full disclosure: I first encountered Paul Kalanithi's book as part of the reading for the 2016 Royal Society science book prize. Although the book wasn't one of those to make the final shortlist, I still found it to be a powerful and affecting piece of literature, not least because Kalanithi did not live to complete his own manuscript. On the basis of this book, he would have been a very gifted medical communicator, writing engagingly and lucidly about his chosen profession of neurosurgery. What makes the account striking and perhaps unique is that the still-young Kalanithi was himself diagnosed with lung cancer, the diagnosis, treatment and eventual outcome of which is treated with unflinching honesty. It's commonplace to talk about the courage of cancer patients, and perhaps not always helpful, but when Kalinithi eventually returns to the gruelling demands of neurosurgery, it's hard not to feel admiration at his mental and physical fortitude, knowing full well the likely progression of his disease. The book was eventually completed by his wife, Lucy Goddard Kalanithi.

Henry Marsh is a brain surgeon who has achieved a modest degree of celebrity thanks to television appearances. His two memoirs, published over the last few years, document the ups and downs of his career and his transition - sometimes uneasy - to a life of somewhat discontented retirement. Along the way he works to assist neurosurgical colleagues in the Ukraine and Nepal, not always with entirely positive results. Throughout the memoirs, Marsh is tormented by difficult ethical considerations, constantly balancing the risks of surgery against the likely outcomes and the anticipated quality of life.

Near the end of the second book, Admissions, Marsh makes an impassioned case for right-to-die legislation. It makes for uncomfortable and challenging reading, but few professionals will have been confronted with the actualities of end-of-life care and mortality as often as a brain surgeon, and it is hard not to be swayed by Marsh's case.

Westaby is a heart surgeon and a friend of Henry Marsh, and despite their rather different backgrounds, there's a distinct similarity of tone and surgical methodology running through the writings of both authors. They have each come up through the NHS in the last forty years; both bear witness to the triumphs and failures of that organisation; both seem at times to be righteously enraged by the slow accretion of bureaucracy and privatisation, choking and fragmenting the very institution they both served and loved. Both surgeons seem driven to form a personal, human connection with their patients, over-joyed when procedures work well, intensely saddened and troubled when the outcomes are not as positive. They are about as far from the image of the cold, detached physician as it is possible to imagine.

Full disclosure: I first encountered Paul Kalanithi's book as part of the reading for the 2016 Royal Society science book prize. Although the book wasn't one of those to make the final shortlist, I still found it to be a powerful and affecting piece of literature, not least because Kalanithi did not live to complete his own manuscript. On the basis of this book, he would have been a very gifted medical communicator, writing engagingly and lucidly about his chosen profession of neurosurgery. What makes the account striking and perhaps unique is that the still-young Kalanithi was himself diagnosed with lung cancer, the diagnosis, treatment and eventual outcome of which is treated with unflinching honesty. It's commonplace to talk about the courage of cancer patients, and perhaps not always helpful, but when Kalinithi eventually returns to the gruelling demands of neurosurgery, it's hard not to feel admiration at his mental and physical fortitude, knowing full well the likely progression of his disease. The book was eventually completed by his wife, Lucy Goddard Kalanithi.

Henry Marsh is a brain surgeon who has achieved a modest degree of celebrity thanks to television appearances. His two memoirs, published over the last few years, document the ups and downs of his career and his transition - sometimes uneasy - to a life of somewhat discontented retirement. Along the way he works to assist neurosurgical colleagues in the Ukraine and Nepal, not always with entirely positive results. Throughout the memoirs, Marsh is tormented by difficult ethical considerations, constantly balancing the risks of surgery against the likely outcomes and the anticipated quality of life.

Near the end of the second book, Admissions, Marsh makes an impassioned case for right-to-die legislation. It makes for uncomfortable and challenging reading, but few professionals will have been confronted with the actualities of end-of-life care and mortality as often as a brain surgeon, and it is hard not to be swayed by Marsh's case.

Westaby is a heart surgeon and a friend of Henry Marsh, and despite their rather different backgrounds, there's a distinct similarity of tone and surgical methodology running through the writings of both authors. They have each come up through the NHS in the last forty years; both bear witness to the triumphs and failures of that organisation; both seem at times to be righteously enraged by the slow accretion of bureaucracy and privatisation, choking and fragmenting the very institution they both served and loved. Both surgeons seem driven to form a personal, human connection with their patients, over-joyed when procedures work well, intensely saddened and troubled when the outcomes are not as positive. They are about as far from the image of the cold, detached physician as it is possible to imagine.

I adored the writings of Oliver Sacks - I read almost all of his popular books - but found this autobiography almost too painful to approach in the immediate aftermath of his death in 2015. After two years, I felt I could return to it, and it's a glorious capstone to his writings, candid and generous in equal parts. Sacks' life has always been a thread in his medical stories, and if you have read Uncle Tungsten, his earlier autobiographical account of his intense love of chemistry, you will pick up on a certain amount of common ground as Sacks relates his upbringing in a bustling, loving Jewish household in London, surrounded by encouraging parents, devoted aunts and uncles, bright siblings and an environment of intense intellectual stimulation. Sacks moved to North America to pursue his interests, and the early chapters of the book - illuminated by his long, discursive diary entries and letters home - are a colourful snapshot of a time now past, during which Sacks indulged his deep fascination with motor bikes and champion weightlifting, while finding his way in the gay communities of the early nineteen sixties. Along the way, we revisit the fascinating and tragic story of the post-encephelitic patients, recounted in the book Awakenings, and the Robin Williams film of the same name. Sacks was clearly impressed with Williams's depth of engagement in the part, achieving an chameleon-like mimicry of both the patients (thanks to visits to clinical facilities) and Sacks himself, whose mannerisms Williams began to imitate in an almost subconscious fashion. At the time of the film I assumed that Williams bore no resemblance to the real Sacks, but period photos put me right: the casting was uncanny.

Tuesday, 25 July 2017

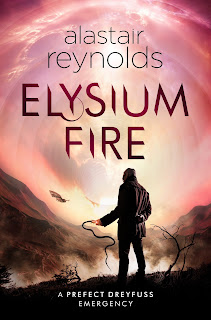

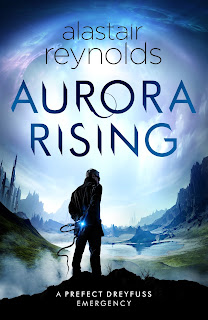

Elysium Fire and a new title for The Prefect

I'm pleased to be able to announce that my next novel will have the title Elysium Fire. Actually the title has been out there for a little while courtesy of various online listings, but at least now I can confirm it (sometimes provisional titles do escape out into the wild) and also offer up the cover artwork, concerning which I'm very happy.

This is a direct sequel to 2007's The Prefect, and although it's been a decade since I completed the earlier novel, the action in this book begins only two years after the events of the first. Although it features the same settings, organisation and main characters of the first, it concerns itself with an entirely different story and is intended to function as a standalone book, requiring no prior knowledge of The Prefect.

While my editor and I were discussing title options for this new novel, none of which seemed to follow on organically from the first, I made the not entirely flippant suggestion that, given the chance, I would jump at the opportunity to retitle The Prefect. Although I still liked the book, over the ensuing decade I'd come to feel that it was one of my weaker titles and was particularly problematic from the standpoint of establishing the idea of the Panoply stories forming a sort of universe within a universe. So, once we had begun to settle on a title for the new book, thoughts turned to the possibility of a fresh identity for the older one, and after some deliberation this is the result:

Obviously I am keen that no one should mistake this for a new novel, so the intention at the moment is that the original title will feature prominently as part of the description on the rear cover (this will be a paperback reissue) while the front cover will have a removable sticker clearly identifying the nature of the book. Online descriptions will also strive to make it clear that this is not an original work, and I'll aim to get the word out at all opportunities between now and the re-issue.

Wednesday, 28 June 2017

Monday, 26 June 2017

Locus award for Revenger

Over the weekend I was delighted to hear that Revenger had won the Locus award for best YA novel. I'm extremely grateful to all who voted for it. This is my second Locus award (after last year's one for Slow Bullets) and it means an awful lot.

Because I had shortlisted entrants in a number of categories, it was suggested that I provide some words to be read out on the night. I've edited them slightly to reflect the eventual outcome, but this should be close to what transpired:

Earlier in the year I had a long and enjoyable conversation with Liza from Locus about the exact category of Revenger, be it YA or otherwise. Liza felt it was YA, whereas (and I'm well aware this will sound like tedious hair-splitting) I'm more inclined to consider it an otherwise standard novel by me that just happened to be a little more YA-approachable, in that I hoped it might be a book that I could have read in my early/mid teens, exactly at the point when I was getting into Niven, Delany, James White, A Bertram Chandler and so on. But at the same time, at least when I was writing it, the book felt as challenging from a compositional point of view as any of my other novels. Where I did want it to mark a modest departure was in terms of concision and pace, in that I wanted to get into the thick of the action quickly and maintain a hectic momentum from that point onward. I also hoped to write a book that was somewhat shorter than its predecessors, drawing on the energy I felt I'd managed to tap into during the writing of the Doctor Who novel. Even so, it still managed to end up being 140,000 words long, which would have been considered a thick novel forty years ago. That wasn't just a one-off experiment for the purposes of Revenger, though, in that I also carried the same process through to the new Prefect novel, which - by the standards of the other book in the Revelation Space universe - is a relatively modest 160,000 words.

Anyway, I mention all this not to quibble with Locus for their award, which is deeply appreciated, but to indicate that I'm not inclined to be too dogmatic about novel categories. If you enjoyed Revenger, I hope that you enjoyed it on its own terms, and if you haven't been persuaded to pick it up because the YA association is off-putting, you might want to give it a go nonetheless.

Because I had shortlisted entrants in a number of categories, it was suggested that I provide some words to be read out on the night. I've edited them slightly to reflect the eventual outcome, but this should be close to what transpired:

Thank you for this award - it means a huge amount to me. Twenty-odd years ago, when I'd barely

had anything published outside of Interzone, Locus was one of the first places to show any interest

in my work beyond the UK, and that validation had an enormous effect on my confidence as a writer,

encouraging me to keep going, and keep trying. I'm still going, and I'm still trying! Thank you all who

voted for Revenger and may I wish you all many more hours of good reading in the

years ahead, and enjoy the rest of the evening. I wish I could be there with you!

Best wishes from Deepest Wales - Al.

Earlier in the year I had a long and enjoyable conversation with Liza from Locus about the exact category of Revenger, be it YA or otherwise. Liza felt it was YA, whereas (and I'm well aware this will sound like tedious hair-splitting) I'm more inclined to consider it an otherwise standard novel by me that just happened to be a little more YA-approachable, in that I hoped it might be a book that I could have read in my early/mid teens, exactly at the point when I was getting into Niven, Delany, James White, A Bertram Chandler and so on. But at the same time, at least when I was writing it, the book felt as challenging from a compositional point of view as any of my other novels. Where I did want it to mark a modest departure was in terms of concision and pace, in that I wanted to get into the thick of the action quickly and maintain a hectic momentum from that point onward. I also hoped to write a book that was somewhat shorter than its predecessors, drawing on the energy I felt I'd managed to tap into during the writing of the Doctor Who novel. Even so, it still managed to end up being 140,000 words long, which would have been considered a thick novel forty years ago. That wasn't just a one-off experiment for the purposes of Revenger, though, in that I also carried the same process through to the new Prefect novel, which - by the standards of the other book in the Revelation Space universe - is a relatively modest 160,000 words.

Anyway, I mention all this not to quibble with Locus for their award, which is deeply appreciated, but to indicate that I'm not inclined to be too dogmatic about novel categories. If you enjoyed Revenger, I hope that you enjoyed it on its own terms, and if you haven't been persuaded to pick it up because the YA association is off-putting, you might want to give it a go nonetheless.

Friday, 23 June 2017

One OK record

It's mildly astonishing that this record is now twenty years old. I bought it, if not on the day it came out, then certainly at the first immediate opportunity, on CD, from a record shop in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, which no longer exists. I think I played it about six times that day. I still think it's remarkably good. What I find surprising is not the length of time that has passed since its release, because - really - quite a lot of things have happened in those two decades - but how fresh and modern it still sounds, how engaged and forward-looking. How bright and exciting and adult. It's been said before but with this record Radiohead threw down a gauntlet which was never really picked up, at least not by any acts of similar commercial reach.

There was a lot of buzz around this record before it came out, a sense of keen anticipation. I think people instinctively knew that it was going to move the boundaries, and it did. I'd heard one track on a compilation CD some months previously, enough to whet the appetite - either Lucky or The Tourist, I can't remember which - but more than that I'd become a fan of the band via the first two albums, which I'd been exposed to via a home-made tape done for me by a friend. Yes, "tapes", they were a thing back then.

Music critics sometimes speak of bands and artists having "imperial phases" - a relatively brief window in a longer career in which they're simply untouchable on all levels. You could debate the inclusion of The Bends (it's very, very good) but for me this is the album that opened Radiohead's imperial phase, and it continued with Kid A and Amnesiac, both of which I regard as phenomenal, peerless records that define and bracket a particular moment in time around the millennium. Then came Hail to the Thief which I remember waiting for which great anticipation, and then not being quite so blown away as I'd hoped. After that came In Rainbows, which I greatly admired, and then The King of Limbs, which again I didn't rate quite so highly. Then, last year, they released A Moon Shaped Pool, which I think is fabulous. I mention these ups and downs not to belittle Radiohead, or suggest that they're past their best, but to reflect on their longevity and willingness to experiment, which I continue to find admirable and exciting. I must have written a great many thousands of words to their music over the last twenty years, so thanks, Thom, Johnny, Colin, Ed and Philip - and long may you run.

Wednesday, 31 May 2017

Two records

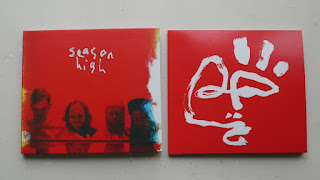

I made a few record purchases during a recent trip to London, and was struck by the similarity in sleeve design of these two albums, both of which I'd recommend:

Both records feature female vocalists, but other than that they're rather distinct. The record on the left is the fifth album by Swedish electronic group Little Dragon, while the record on the right is the debut album by London-based guitar group Pumarosa. The Little Dragon record contains no guitar parts at all, whereas the Pumarosa album is mostly guitar with the odd bit of sequencing or keyboard colour. I bought these albums in Fopp, near Covent Garden, and it was on a much earlier visit to the same shop that saw me buying Little Dragon's second album, Machine Dreams. I hadn't heard a note of the music, but the cover intrigued me and I've always found that to be a generally reliable guide to investigating and discovering worthwhile new music.

I adored Machine Dreams, and bought all the subsequent releases. I liked them so much that I even named a character in one of my stories after the singer, Yukimi. None of the subsequent albums have quite lit my fire as much as Machine Dreams, but there are many beautiful moments on all their records, and I admire Little Dragon for doing what they do, making music that sounds fresh and forward-looking, owing (other than the odd retro synth-sound) very little to the past. I've only given the new release, Season High, a single listen so far but I look forward to discovering its undoubted charms.

I came to the other record by more conventional means. I'd caught a performance by Pumarosa on BBC2's Jools Holland program and within a few bars knew instantly that they were going to be my new favorite thing. At that point I knew next to nothing about the group but I then spent a happy few years catching up with some of their songs on Youtube, and was pleased to discover than an album had just been released. Rather good it is too: exactly the kind of trancey, driving guitar rock that does it for me, alloyed to Isabel Munoz-Newsome's distinctive and swooningly theatrical singing approach, which won't be everyone's cup of tea, but works (in my view) very well in this musical setting. I've read comparisons between her voice and Siouxsie Sioux's, obviously no bad thing if you're of my generation, but that's only one point of reference. I also picked up a bassline that reminded me strongly of Simple Mind's Love Song, but then again, that's one of the most mesmerising basslines in the history of music, so again - no bad thing at all.

Here are the CDs themselves, by the way:

And I commend them both for your listening enjoyment.

Both records feature female vocalists, but other than that they're rather distinct. The record on the left is the fifth album by Swedish electronic group Little Dragon, while the record on the right is the debut album by London-based guitar group Pumarosa. The Little Dragon record contains no guitar parts at all, whereas the Pumarosa album is mostly guitar with the odd bit of sequencing or keyboard colour. I bought these albums in Fopp, near Covent Garden, and it was on a much earlier visit to the same shop that saw me buying Little Dragon's second album, Machine Dreams. I hadn't heard a note of the music, but the cover intrigued me and I've always found that to be a generally reliable guide to investigating and discovering worthwhile new music.

I adored Machine Dreams, and bought all the subsequent releases. I liked them so much that I even named a character in one of my stories after the singer, Yukimi. None of the subsequent albums have quite lit my fire as much as Machine Dreams, but there are many beautiful moments on all their records, and I admire Little Dragon for doing what they do, making music that sounds fresh and forward-looking, owing (other than the odd retro synth-sound) very little to the past. I've only given the new release, Season High, a single listen so far but I look forward to discovering its undoubted charms.

I came to the other record by more conventional means. I'd caught a performance by Pumarosa on BBC2's Jools Holland program and within a few bars knew instantly that they were going to be my new favorite thing. At that point I knew next to nothing about the group but I then spent a happy few years catching up with some of their songs on Youtube, and was pleased to discover than an album had just been released. Rather good it is too: exactly the kind of trancey, driving guitar rock that does it for me, alloyed to Isabel Munoz-Newsome's distinctive and swooningly theatrical singing approach, which won't be everyone's cup of tea, but works (in my view) very well in this musical setting. I've read comparisons between her voice and Siouxsie Sioux's, obviously no bad thing if you're of my generation, but that's only one point of reference. I also picked up a bassline that reminded me strongly of Simple Mind's Love Song, but then again, that's one of the most mesmerising basslines in the history of music, so again - no bad thing at all.

Here are the CDs themselves, by the way:

And I commend them both for your listening enjoyment.

Friday, 19 May 2017

Chris Cornell, 1964 - 2017

Scrolling through a small list of files, Sheng settled on some mid-period rock he’d copied over from Parry Boyce’s much larger music library. Some of the other miners mocked Parry’s tastes, but the way Sheng saw it, if you needed something to cut through the background drone of generators and pumps, there was not much out there to beat amped guitars, hammering drums and screaming vocals, no matter when it was recorded. It was driving music, for the ultimate drive.

‘Tommorow begat tomorrow…’ Sheng sang along, music filling his helmet like a derailing freight train. With the long cylinder of the lubricator nozzle unclipped, he pulled some mean guitar shapes like the secret ax hero he’d always imagined he could have been. He knew he looked ridiculous, making those moves in an ancient orange Orlan 19, bulked out with panniers, but his only audience was ancient alien machinery. Sheng considered it a reasonably safe bet that the ancient alien machinery had no particular opinion on the matter.

Sheng was not quite right in that assumption.

‘Tommorow begat tomorrow…’ Sheng sang along, music filling his helmet like a derailing freight train. With the long cylinder of the lubricator nozzle unclipped, he pulled some mean guitar shapes like the secret ax hero he’d always imagined he could have been. He knew he looked ridiculous, making those moves in an ancient orange Orlan 19, bulked out with panniers, but his only audience was ancient alien machinery. Sheng considered it a reasonably safe bet that the ancient alien machinery had no particular opinion on the matter.

Sheng was not quite right in that assumption.

(from Pushing Ice)

Wednesday, 19 April 2017

Thursday, 13 April 2017

Kirk Drift

If you have a little time on your hands I commend this excellent Strange Horizons article by Erin Horakova on our changing (and inaccurate) perception of the character of Captain Kirk:

http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/columns/freshly-rememberd-kirk-drift/

It struck a chord with me because I had a related, if parallel, set of thoughts after watching the entire run of the original series. The popular culture cliche is that William Shatner is/was a somewhat crude and mediocre actor with a peculiar sense of ... timing ... in the delivery of his dialogue, and I went into the re-watch to some extent pre-conditioned by this notion. Regardless of the quality of the individual episodes, though, I quickly found myself wondering when this legendary bad Shatner was going to turn up, because all I was seeing - right from the outset - was an efficient and convincing portrayal of a man in a complex, demanding position of authority. Shatner isn't just much better at playing Kirk than the popular myth would have it, but the character itself is also much more plausibly drawn than the supposed brash womaniser of the insidious meme.

Erin Horakova dismantles this false Kirk in expert fashion, while lobbing a few well-earned potshots at the reboot films.

Monday, 10 April 2017

The Power of the Daleks (1966)

I'm only four episodes into this six parter, one of the stories thought lost to time, but which has now been restored with animated visuals and the original soundtrack.

Although the visual reconstruction is cheap and cheerful, it's still remarkably effective at taking you into the story, and while I wouldn't say you ever forget you're watching an animation, it certainly doesn't impede one's enjoyment of this compelling, intelligent and surprisingly adult adventure.

I have no recollection of the Troughton years, and would only have been less than a year old at the time of this transmission, his first story after regeneration. Unfortunately the Troughton era suffered particularly badly from deleted tapes, and I've still not seen enough of his stories to have a clear sense of his personality as the Doctor. In this adventure, the Doctor's persona is even more unstable than usual and Troughton was evidently trying on a variety of tones as he settled into the role.

What's striking about the story, especially in regard to some of the later plots, is the low-key realism of the political machinations going on inside the Vulcan colony, with the Doctor arriving just as a brooding power struggle threatens to erupt. The character exchanges are terse and restrained, the atmosphere one of controlled bureaucratic paranoia and veiled threats, more in keeping with Le Carre than something supposedly aimed at children and aired during a cosy tea-time transmission slot.

The Daleks are excellent - always at their best when they are at their slyest, as in this story, pretending to be helpful robot servants. And the scenes in the Dalek production line, as raw Dalek organisms are ladled - none too gently - into the open receptacles of new machines - are chilling. I didn't realise that we'd seen the "insides" of a Dalek this early in the series. It's accurate to the original filmed sequences, too, as the animations are based around production stills that were shot during the filming of each episode.

Recommended for all fans of Daleks and Doctor Who.

Although the visual reconstruction is cheap and cheerful, it's still remarkably effective at taking you into the story, and while I wouldn't say you ever forget you're watching an animation, it certainly doesn't impede one's enjoyment of this compelling, intelligent and surprisingly adult adventure.

I have no recollection of the Troughton years, and would only have been less than a year old at the time of this transmission, his first story after regeneration. Unfortunately the Troughton era suffered particularly badly from deleted tapes, and I've still not seen enough of his stories to have a clear sense of his personality as the Doctor. In this adventure, the Doctor's persona is even more unstable than usual and Troughton was evidently trying on a variety of tones as he settled into the role.

What's striking about the story, especially in regard to some of the later plots, is the low-key realism of the political machinations going on inside the Vulcan colony, with the Doctor arriving just as a brooding power struggle threatens to erupt. The character exchanges are terse and restrained, the atmosphere one of controlled bureaucratic paranoia and veiled threats, more in keeping with Le Carre than something supposedly aimed at children and aired during a cosy tea-time transmission slot.

The Daleks are excellent - always at their best when they are at their slyest, as in this story, pretending to be helpful robot servants. And the scenes in the Dalek production line, as raw Dalek organisms are ladled - none too gently - into the open receptacles of new machines - are chilling. I didn't realise that we'd seen the "insides" of a Dalek this early in the series. It's accurate to the original filmed sequences, too, as the animations are based around production stills that were shot during the filming of each episode.

Recommended for all fans of Daleks and Doctor Who.

Friday, 31 March 2017

Star Trek: The Next Generation rewatch - Encounter at Farpoint

Having recently finished watching the complete run of the remastered episodes of the original series of Star Trek, I felt like diving into one of the later series. The release of the Next Generation in fully remastered format on Blu-Ray seemed a good place to start, so I bought the complete set with the intention of watching from the start.

I've loved Star Trek since I was tiny. As a child, watching a black and white television set in Cornwall, there were two series that particularly fascinated me. One was Star Trek, and the other The Virginian. Whether this accounted for a lifelong affection for space and Westerns/cowboys/horses, I'll leave to the psychologists, but there's no doubting the vivid mark that Star Trek left on me. A few years later, after we had moved from Truro but were still living in Cornwall, two further pivotal events helped cement my feelings for Star Trek.

The first was getting the Aurora kit of the Enterprise:

I think it lasted about three weeks before the nacelles snapped off, but what a glorious three weeks they were. Surely this is the weirdest spaceship design to ever attain iconic status? From an engineering/physics point of view it makes no sense whatsoever, but it just looks right and for my money few of the later designs have quite hit the same marks.

The second pivotal event was watching Star Trek in colour for the first time, at my grandmother's house in Barry. Even now, the original series looks very colourful, from the uniforms to the set designs to the use of lighting filters in many of the shots. In the early seventies, having been conditioned by exposure to the episodes in black and white, it was a real jolt to the eyeballs. The remastered episodes look very good, incidentally, with some sympathetic use of CGI to update some of the effects and sets.

Star Trek was often on television in the early seventies. During school vacations, the episodes were broadcast in the morning in a format called "Holiday Star Trek", which I've taken to mean episodes which were deemed not to contain any overtly adult or upsetting themes, although whether that was actually the case I don't know, as it just seemed like a random grab-bag of stories to me.

My admiration for the series was further reinforced by an article which appeared in Speed & Power magazine around 1974, consisting of a two-page feature which brought us exciting facts like exactly how big and fast was the Enterprise. Given that the Enterprise was deemed to be a bit less than a thousand feet long, I then became obsessed with relating this dimension to real world objects, such as the television masts near our home. I'd been told they were a thousand feet tall so I tried to imagine the Enterprise standing on its end, next to one of these masts. But that didn't seem anywhere near big enough to me. I had a similar problem with Captain Nemo's submarine -*.

Anyway, that's enough rose-tinted nostalgia. Fast forward to 1988. Star Trek was coming back onto television and by some means that I don't quite recall, the pilot episode was available to be shown in one of the common rooms at Newcastle University. Thus, those of us who cared gathered round on plastic chairs to watch "Encounter at Farpoint". At that point, there had been a few hints about what to expect. We knew that the main captain was to be played by a bald British actor, that there would be an android, a Klingon, and so on. But in those pre-internet days there was far less in the way of "spoilers", so I remember going into the screening with very little expectation of what to expect.

The prevailing view, as far as I'm aware, is that the pilot was an underwhelming opener to what would prove to be a weak couple of seasons, before The Next Generation really found its strengths. That certainly chimes with my recollections of that screening, in that the early appearance of "Q" - the recurring alien trickster figure - seemed to harken back to some of the hoariest episodes of the original run, in which super-powerful alien demigods were forever popping up on the Enterprise's bridge, usually in some sort of period costume.

Rewatching "Encounter..." now, though, after a gap of nearly thirty years, brings a more balanced view. It's not actually that terrible. The pace is slow, and the stakes are never more than vague, but perhaps it needed that narrative space to allow scope for the characters to establish themselves. And, allowing for some stiffness in their interactions, there are welcome moments when the pilot takes time to allow the characters to present themselves, which perhaps wouldn't be the case if there was a lot more running around and shouting.

Significantly, if you've splashed out on the Blu-Rays, it looks magnificent. They did an amazing, and by all accounts expensive and painstaking job, in restoring this series. The effort is worthwhile, because - allowing for the inevitable production economies of indoor sets masquerading as planetary locations - it holds up very, very well for a show made thirty years ago.

Above all else, it's a reminder that there was a time when Star Trek was actually forward-looking, not afraid to move beyond its past.

*- Verne describes the Nautilus as being seventy metres long. I think it some point I must have encountered a mistranslation which put the length at seventy feet, because I remember being convinced that this was nowhere near big enough.

I've loved Star Trek since I was tiny. As a child, watching a black and white television set in Cornwall, there were two series that particularly fascinated me. One was Star Trek, and the other The Virginian. Whether this accounted for a lifelong affection for space and Westerns/cowboys/horses, I'll leave to the psychologists, but there's no doubting the vivid mark that Star Trek left on me. A few years later, after we had moved from Truro but were still living in Cornwall, two further pivotal events helped cement my feelings for Star Trek.

The first was getting the Aurora kit of the Enterprise:

I think it lasted about three weeks before the nacelles snapped off, but what a glorious three weeks they were. Surely this is the weirdest spaceship design to ever attain iconic status? From an engineering/physics point of view it makes no sense whatsoever, but it just looks right and for my money few of the later designs have quite hit the same marks.

The second pivotal event was watching Star Trek in colour for the first time, at my grandmother's house in Barry. Even now, the original series looks very colourful, from the uniforms to the set designs to the use of lighting filters in many of the shots. In the early seventies, having been conditioned by exposure to the episodes in black and white, it was a real jolt to the eyeballs. The remastered episodes look very good, incidentally, with some sympathetic use of CGI to update some of the effects and sets.

Star Trek was often on television in the early seventies. During school vacations, the episodes were broadcast in the morning in a format called "Holiday Star Trek", which I've taken to mean episodes which were deemed not to contain any overtly adult or upsetting themes, although whether that was actually the case I don't know, as it just seemed like a random grab-bag of stories to me.

My admiration for the series was further reinforced by an article which appeared in Speed & Power magazine around 1974, consisting of a two-page feature which brought us exciting facts like exactly how big and fast was the Enterprise. Given that the Enterprise was deemed to be a bit less than a thousand feet long, I then became obsessed with relating this dimension to real world objects, such as the television masts near our home. I'd been told they were a thousand feet tall so I tried to imagine the Enterprise standing on its end, next to one of these masts. But that didn't seem anywhere near big enough to me. I had a similar problem with Captain Nemo's submarine -*.

Anyway, that's enough rose-tinted nostalgia. Fast forward to 1988. Star Trek was coming back onto television and by some means that I don't quite recall, the pilot episode was available to be shown in one of the common rooms at Newcastle University. Thus, those of us who cared gathered round on plastic chairs to watch "Encounter at Farpoint". At that point, there had been a few hints about what to expect. We knew that the main captain was to be played by a bald British actor, that there would be an android, a Klingon, and so on. But in those pre-internet days there was far less in the way of "spoilers", so I remember going into the screening with very little expectation of what to expect.

The prevailing view, as far as I'm aware, is that the pilot was an underwhelming opener to what would prove to be a weak couple of seasons, before The Next Generation really found its strengths. That certainly chimes with my recollections of that screening, in that the early appearance of "Q" - the recurring alien trickster figure - seemed to harken back to some of the hoariest episodes of the original run, in which super-powerful alien demigods were forever popping up on the Enterprise's bridge, usually in some sort of period costume.

Rewatching "Encounter..." now, though, after a gap of nearly thirty years, brings a more balanced view. It's not actually that terrible. The pace is slow, and the stakes are never more than vague, but perhaps it needed that narrative space to allow scope for the characters to establish themselves. And, allowing for some stiffness in their interactions, there are welcome moments when the pilot takes time to allow the characters to present themselves, which perhaps wouldn't be the case if there was a lot more running around and shouting.

Significantly, if you've splashed out on the Blu-Rays, it looks magnificent. They did an amazing, and by all accounts expensive and painstaking job, in restoring this series. The effort is worthwhile, because - allowing for the inevitable production economies of indoor sets masquerading as planetary locations - it holds up very, very well for a show made thirty years ago.

Above all else, it's a reminder that there was a time when Star Trek was actually forward-looking, not afraid to move beyond its past.

*- Verne describes the Nautilus as being seventy metres long. I think it some point I must have encountered a mistranslation which put the length at seventy feet, because I remember being convinced that this was nowhere near big enough.

Monday, 27 March 2017

Thursday, 23 March 2017

New one in

So I've delivered a new novel. We have a possible title, but it's still subject to discussion and may well change, so I won't mention it just yet. What I can say is that the new book is the first novel-length work to be set in the Revelation Space universe since 2007, and is also a sequel to The Prefect. Despite the decade-long gap beween these books, this one is set only two years after the last and features a large number of recurring characters. Nonetheless I hope that it will be capable of being read independently of the first.

As far as I am aware publication is not likely to happen until early 2018.

As far as I am aware publication is not likely to happen until early 2018.

Monday, 20 March 2017

Strasbourg

I was in Strasbourg the week before last, delivering a lecture to the International Space University. Opportunities such as this, which offer the chance to meet with friends old and new, as well as visiting previously unfamiliar parts of the world, are one of the great blessings of being a professional writer. I also have the benefit of having had what is considered to be an interesting career trajectory, having gone from full-time scientist to full-time author. Time and again, opportunities have come my way that would perhaps be rarer were I not to have had this supposedly unusual dual citizenship in the worlds of the arts and sciences. I am extremely grateful.

I had not visited Strasbourg before, so my wife and I made a short stay of it after I had delivered my lecture. Strasbourg was enchanting, a beautiful, compact city with wonderful winding streets and canals, its architecture betraying a long and turbulent history complicated by Strasbourg's close proximity to the German border. Indeed, Strasbourg has been both German and French in its time, as the border shifted one way or the other.

Inevitably, it was impossible to visit the official seat of the European Parliament and not be reminded sharply of the imminent reality of Brexit, now seemingly likely to be driven through in the hardest of all possible terms. I wrote about Brexit before the referendum, articulating - to the best of my abilities - my reasons for thinking that Britain would be better off remaining within the EU. My position was admittedly based as much on emotion as logic, but I see no need to apologise for that. Emotions have been running high for as long as the referendum has been on the table, on all sides of the debate. Why not? It's an emotive topic, cutting across real lives and real experiences. I lived and worked in the EU, I benefited strongly from the free movement of workers across its borders; I even claimed unemployment benefit from the Dutch government when I was without work. I see myself as European in outlook and temperament. My wife is an EU national. We now live in the UK, and for at least half a decade considered our future settled. We were content to make our future in a country we both regarded as open, tolerant and forward-looking. All of that has changed since June.

And yet, with a certain fatalism, I now accept the reality of Brexit. Barring some terrorist or military incident completely shifting the political landscape, there seems no way that it is not going to happen. Reasonable voices have been raised against it, and their positions summarily dismissed in the most insulting of terms - enemies of the people, remoaners, and so on.

But acceptance need not mean an abdication of feeling. I "accept" Brexit in the same spirit that, if you are strapped to a table and someone is sawing your leg off, you "accept" that it will continue. Indeed, once started, the process - however damaging - had better be seen through to its dispiriting conclusion. I am convinced now that our leaders have already poisoned the discourse so thoroughly that it would be difficult for the UK to settle back into its former position within Europe, even if Brexit were immediately abandoned.

It won't be, though. Like Basil Fawlty, bashing his head against the desk, it seems this is the reality we're stuck with.

Friday, 17 March 2017

John Lever

I was browsing the Guardian's music section when I saw the sad and shocking news that drummer John Lever had died. Never famous, Lever was nonetheless the driving force behind one of the enduring musical obsessions of my life, the underrated but quietly influential band The Chameleons.

They were active in their initial incarnation for only five or six years, enough to put out a few singles, cut three albums, and record a number of radio sessions. They were completely unknown to me until the release in 1986 of the single Tears from their third album. I heard it played - and get mostly slagged off, I seem to remember - on one of those jukebox jury type programs on Radio 1. Something of its driving, start-stop energy must have stayed with me, though, because when I later saw the 12" ep of the single, I snapped it up. I played little else that summer. I still have that 12" and I still play it regularly. It's magnificent.

I bought the album when it came out, which disconcertingly enough had a completely different version of the song on it, but which I came to love just as much as the single. I suppose you'd call it moody indie rock now, but at the time the only people I knew who had even heard of this band were some of my goth friends, and thanks to them I managed to hear the earlier singles, as well as the first two albums. Over the next few years, these records (and the various spin-offs by the band members, after the group disbanded) were rarely off my turntable. Nobody else sounded like them. You could hear their influence in lots of bands who came later,, but no one seemed to come close to the same magical alchemy of chiming guitars, soaring vocals and god's own drum sound. Someone once described John Lever's playing style as sounding like a man trying to smash a lathe to pieces.

I mean, have a listen to this:

When I first heard the above track - Home is where the Heart is - I felt like it was a piece of secret music I'd been waiting my whole life to hear. I played it last week, as it happened, just because, and it still sounds as huge and terrifying and apocalyptic as it did in 1987, when I encountered it for the first time. I mean, listen to those drums. That's the end of the world right there - and bloody hell it sounds good.

I thought I'd blown my chances of ever seeing The Chameleons by dint of coming to them a few months too late. They were gone by 1987, splitting up in acrimony after bad deals and the death of their manager. They deserved much better, and there was a second bite at the cherry around 2000-2001, when they reformed for some dates and a new record. I caught them twice, and they were as great and thrilling as I'd hoped. Both sets commenced, I recall, with the titanic A Person Isn't Safe, from their first album.

Thank you, John Lever, for laying down your drum sounds on some of the greatest records almost no one has ever heard.

They were active in their initial incarnation for only five or six years, enough to put out a few singles, cut three albums, and record a number of radio sessions. They were completely unknown to me until the release in 1986 of the single Tears from their third album. I heard it played - and get mostly slagged off, I seem to remember - on one of those jukebox jury type programs on Radio 1. Something of its driving, start-stop energy must have stayed with me, though, because when I later saw the 12" ep of the single, I snapped it up. I played little else that summer. I still have that 12" and I still play it regularly. It's magnificent.

I bought the album when it came out, which disconcertingly enough had a completely different version of the song on it, but which I came to love just as much as the single. I suppose you'd call it moody indie rock now, but at the time the only people I knew who had even heard of this band were some of my goth friends, and thanks to them I managed to hear the earlier singles, as well as the first two albums. Over the next few years, these records (and the various spin-offs by the band members, after the group disbanded) were rarely off my turntable. Nobody else sounded like them. You could hear their influence in lots of bands who came later,, but no one seemed to come close to the same magical alchemy of chiming guitars, soaring vocals and god's own drum sound. Someone once described John Lever's playing style as sounding like a man trying to smash a lathe to pieces.

I mean, have a listen to this:

When I first heard the above track - Home is where the Heart is - I felt like it was a piece of secret music I'd been waiting my whole life to hear. I played it last week, as it happened, just because, and it still sounds as huge and terrifying and apocalyptic as it did in 1987, when I encountered it for the first time. I mean, listen to those drums. That's the end of the world right there - and bloody hell it sounds good.