I’ve never pretended to keep up with the short fiction field

inside science fiction – let alone the all-encompassing genre of the fantastic

– but there was a time when I did at least read all the magazines to which I

subscribed, and also made an effort to digest the contents of the various

Year’s Best anthologies when they came round. When I first subscribed to

Interzone, a staggering thirty years ago, it was no problem at all to read each

issue before the next arrived. I was a student, I had no television, no

computer, limited reading funds and only so much money to spend down the pub.

Then again, it was only a quarterly and not a thick one at that. The magazine

eventually moved to a bi-monthly, and then a monthly schedule. Although the

increased frequency was good for the likes of me, trying to place my stories,

it meant that I soon found myself struggling to finish each issue before the

next arrived. That said, I’d always read two or three stories from each issue,

especially if they were by favorite writers. Much the same was true of

Asimov’s, the only other SF magazine to which I’ve had a long-standing

subscription. I continue to subscribe to both Interzone and Asimovs, and in

addition I take the dark/weird/horror magazine Black Static, also published by

Interzone’s TTA Press.

At some point, though, my reading tapered off to the point

of virtual non-existence, and I found myself increasingly reliant on Year’s

Best round-ups, as well as general in-genre buzz, to keep me abreast of what

was worth reading. Even then, I was no longer reading the Year’s Best

anthologies from cover to cover, and I’ll readily confess that there are many

highly praised, award winning writers of whom I’ve yet to read a single word.

Obviously that’s not good enough, so what to do about it? Over on her blog,

Nina Allan has suggested that we could all do our bit for the short fiction

scene by reading just twenty pieces a year, a target that seems perfectly

achievable with a bit of discipline. I’m well aware, of course, that many people

will be reading hundreds of short stories this year – but if you’re one of

them, you’re not the problem. It’s the slackers like me who need incentivising.

At this point, something else struck me. Back when I started

breaking into short fiction, in the golden dawn of those pre-web days, the

field was considerably smaller. The upside of that was that any given story

tended to get at least some measure of recognition in terms of reviews and

letters. The BSFA had a regular short fiction section in one of its magazines,

as did Locus, and both of these venues were pretty comprehensive in their

coverage. In addition, Interzone (and indeed the other magazines) had active

letters pages which often featured biting commentary on the stories that had

appeared in preceeding issues.

Compare and contrast with the situation now, in which there

are far too many short stories published for any of the venues to offer more

than cursory coverage (sometimes no more than a line or two, if you’re lucky).

In addition – and there are exceptions – a lot of short fiction reviewing just

isn’t very insightful. At its worst, I’d call it no more than extended plot-quibbling – a template

approach in which a story is summarised, some of its premises are argued

against, the characters are stuffed into one of two handy bins marked

sympathetic or unsympathetic, and if the story’s lucky it’s called well-written

or readable. Very little tends to be said about style, language, voice, tense,

point of view, pace, subtext, and so on. Well-written is a useless, content-free

descriptor – if you’re reviewing something, it tells us almost nothing unless

we know your tastes. Readable is no better. Of course it’s readable. It’s

printed legibly, using a sequence of recognised lexical symbols that your brain

has learned to decode. If it isn’t, try turning the magazine the other way up…

The fault is not necessarily with the reviewers, who don’t

always have the opportunity to go into more than the barest bones of a plot

summary. On the other hand, wouldn’t it be good to get a little additional

perspective on the story, attempting to look at the artistic choices, good or

otherwise, beyond the surface furniture of the narrative? The online magazine

Strange Horizons has been doing something like this, with some very thorough analyses of recent stories, but as commendable as these exercises

are, it’s clearly not practical on a systematic, issue by issue approach. With

that in mind, therefore – and while I’ve neither the time nor the inclination

to dig into a given story in anything like that degree of thoroughness – I

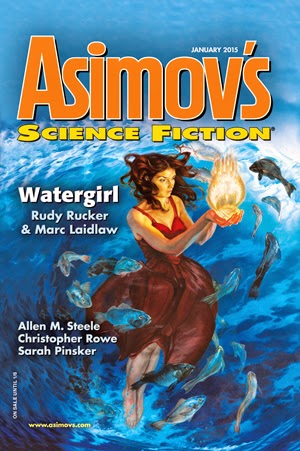

thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at the contents of Asimov’s

Science Fiction magazine across a number of issues. I’ll make no rash promises

– I’ve no real idea how my work is going to pile up as we go through the year,

let alone what else life has in store – but while it’s feasible, I’ll aim to

take a look at each issue starting with the January 2015 magazine.

A couple of remarks, before we get into the stories. The

field would be poorer without Asimov’s. It’s something worth celebrating that

the magazine continues to put out issues, month in, month out, despite existing

in a vastly different literary and economic landscape to the one that was

around when it started. I’ve had a few stories in the magazine and it was

thrilling to see my name on the table of contents. I also know what it’s like

to sweat over a story, pour your heart and soul into it, and then see it

ignored, dismissed or savaged by a short fiction reviewer. That said, the very

worst story I’m likely to look at in a year of Asimov’s is very unlikely to be

as bad as the worst story I’ve ever had published, and chances are it’ll

probably be quite a bit better. I subscribe to Asimov’s because its fiction is

generally to my taste, and my reaction to a story I can’t get on with is more

likely to be indifference or befuddlement than outright dislike. Equally, if

I’m critical of a particular story, that doesn’t mean I won’t be enthusiastic

about the next one by that author. The writers here have already done well by

selling their stories to a respected paying market, and if I don’t like a

particular piece, chances are that someone else will. Of the authors under

consideration here, I’ve only met Allen M Steele and Steele himself has done me

a few kindnesses over the years. But I’ll do my best to offer fair assessments

of the stories, on the assumption that if we agree that short fiction is

important, we should also agree to be honest about it.

So – let’s take a look at the fiction in the January 2015 issue

of Asimov’s Science Fiction.

The first story is “The Unveiling” by Christopher Rowe. It’s

a short story about a group of blue collar employees tasked with cleaning up

some statues on Castellon, an alien planet, in advance of a big civic event.

The workers have to contend with shoddy equipment and awful labour conditions,

and we’re given enough information to decide for ourselves that Castellon is

run by an autocratic, oppressive government. Tayne, the protagonist in charge

of the work crew, has an odd encounter in the sculpture garden with an offworld

artist who appears to be responsible for one of the statues. There’s a certain

ambiguity as to what happens next, unless I’m missing something blindingly

obvious, but Tayne eventually ends up in deep water and takes decisive action

to protect the rest of the work crew from the consequences. The story’s told in

the third person, past tense, with a mostly tight focus on Tayne, albeit salted

with occasional authorial interjections to tell us stuff about the planet and

its society that Tayne would presumably have internalised long ago. There’s a

lot of stuff about squalid working conditions and knackered equipment – the

overall tone of the piece is, I think, quite intentionally drab, but it does

make for a somewhat colourless, joyless reading experience. There’s not really

anything going on at the level of language or dialogue to liven things up all

that much, but on the plus side the characters are well drawn, their

interactions feel plausible, and we get a sense of the wider economic system in

which they are imprisoned.

I mentioned the tight focus on Tayne, but at the end there’s

a shift of viewpoint which doesn’t feel as structurally satisfying as one might

wish. A fixed viewpoint isn’t some absolute sacred cow, and writers should feel

at liberty to violate it when the needs of the story dictate as much – Dickens

felt no inhibitions, after all. But a short story really needs to feel

thematically and artistically integrated, a thing unto itself, and bolting a new

viewpoint on right at the end creates a feeling of lopsidedness, like a house

with an odd extension. Very few successful short stories have more than one

viewpoint, and there’s a reason for that.

Next up is the cover story, “Watergirl”, by Rudy Rucker and

Marc Laidlaw. It’s one of their long-running series of Zep and Delbert surfpunk

stories. I’ve always liked Rucker’s stuff and I remember reading a couple of these collaborative pieces back when

I was living in Scotland, and that’s getting on for a quarter of a century ago.

My recollection is that the tone of those earlier stories was pretty much

exactly the same as this new novelette: a kind of psychedelic, trippy

confection of surfer lore, chaos theory and quantum physics. It’s the kind of

thing that could be wearying in long doses, like an extended repeat of Wayne’s

World – or even Bill & Ted – but “Watergirl” manages to feel fresh enough

and despite its length it doesn’t outstay its welcome. Of all the stories in

this issue, “Watergirl” is the only one that attempts to do anything

distinctive with its prose, filtering the tale through a druggy, laid-back haze

of chilled-out surfer speak, and more or less sustaining the affect throughout.

Nothing much is at stake here – there’s some stuff about dodgy real-estate

deals in Hawaii, some other stuff about a dead surfer chick who may or may not

have been bumped off, and finally some SF gimmickry about a device that can

imprint sentience on water. The local rather than global focus actually works

to the story’s benefit, though, and there’s some gorgeously surreal imagery

near the end, as the villain of the piece is dispatched by suitably creative

means. Rucker and Laidlaw take pains to differentiate their (admittedly

cartoonish) characters, as well, so they don’t all sound like each other.

Onto another short story now, in the form of “Ninety-five

Percent Safe” by Caroline Yoachim. The set-up here is that a wormhole links

Earth to an extrasolar planet, but there’s a one in twenty chance that you

won’t come out the other end – hence the title of the piece. It’s one of two

stories in the issue told from juvenile viewpoints – the other’s coming up

later - and in common with “The Unveiling” it opts for a tight viewpoint, third

person, past tense narration. Like that earlier piece, it’s almost

unremittingly grey, but this time the greyness is consciously foregrounded,

there in the architecture and clothing. Our protagonist is Nicole, daughter of

a family who haven’t quite decided whether or not to take their chances with

the wormhole, even though there’s the prospect of a somewhat better life on the

other side of it – provided they can beat those odds. Tonally, it’s pitched at

exactly the casual, undemanding level you’d expect of a middlebrow YA story –

there’s nothing remotely adventurous going on with the language or imagery –

and while it’s fine in and of itself, it makes me wonder quite what it’s doing

in what is otherwise an adult-orientated science fiction magazine.

Aside from issues of tone, a problem with short stories is

that emotional arcs can feel absurdly compressed if they’re not handled

elegantly. A novelist can trace the stages of bereavement across whole

chapters, even a whole novel, but the beats of a short story consist of

sections and paragraphs, not chapters. When Nicole learns of the death of her

mother – occasioned, ultimately, by Nicole’s own actions – she goes from shock,

anger, remorse, to a kind of bittersweet acceptance, in less than one page.

It’s not that the arc itself is implausible, or rings emotionally false, but

the constraints of the form can’t help but engender bathos rather than pathos.

It’s a rare story that needs to be longer, but an intervening scene – however

slight – might have helped establish a sense of time’s passing, and therefore

made Nicole’s adjustments seem more naturalistic.

The next story is quite a bit darker, and almost jarringly

different in its themes and handling. “Candy from Strangers” by Jay O’ Connell

is just barely science fiction, in that one of the plot points turns on the

protagonist being able to harvest a vast amount of personal information about

the object of his fascination, a woman who might be about to jump in front of a

train. There’s some stuff about smart drugs, offshore BlackNet servers, and we

later learn that the protagonist Morgan has himself survived a botched suicide

attempt – at some considerable cost, with advanced medical intervention – but

beyond that the science fictional elements are sparse, and what with its keen

sense of place, you could almost set the story in present day Boston.

But the argument that a story must contain some science

fiction thing – that it shouldn’t be easily reducible to another genre by the

mere substitution of tropes (eg spaceships for horses, rayguns for sixguns) –

has always struck me as a bit facile, and I’d much rather assess a story on its

emotional heft as a thing in its own right, regardless of the integrity or

otherwise of its conceptual elements. In that regard, “Candy from Strangers”

works perfectly well on its own terms, and Morgan’s arc is satisyingly

described. It’s a polished piece that knows exactly what it’s doing.

The next piece – “Butterflies” by Peter Wood - is the one

that left me most puzzled, as despite three reads I couldn’t quite get to grips

with it. It’s a perfectly pleasant homage to the monster movies of the fifties,

complete with reference to mutation and atomic tests – but updated to the

present, with some nicely barbed stuff about modern gender norms and academic

politics. Maybe that’s all there is to it: a recasting of familiar tropes in an

up to date setting. The tone is light-hearted without ever spilling over into

actual comedy, and there’s a nicely ironic reversal at the end. Perhaps I’m

looking too hard, trying to find a depth that was never meant to be there. In

any case, there’s nothing wrong with the story or the telling, and perhaps I’m

just not sufficiently versed in those monster movies to get the larger point.

The penultimate story is another story with a juvenile

protagonist, and again – like “Ninety Five Percent Safe” – it seems to be aimed

at a YA reader. But “Songs in the Key of You” by Sarah Pinsker does have a

certain charm to it, and there’s a lovely moment in which the bullied Aisha

takes ownership of a humiliating incident in the school dining hall by choosing

her own nickname. The science fictional premise here is wafer-thin: kids (and

adults) have these bracelets which generate musical melodies tuned to the

personality of the wearer, so that everyone gets their own signature theme,

like characters in a sitcom. Aisha can’t afford one of the bracelets, so she

had to hum out her own tune. As it happens, though, she’s really good at coming

up with the tunes so she ends up creating melodies for the other kids. And

that’s your story. It sounds thin but it’s a short piece that isn’t claiming to

offer anything more than a snapshot in our young protagonist’s life, and on

that level you can’t really fault it. But – and not to get into a larger

argument about the rights and wrongs of YA fiction – it’s not really what I

want from an adult science fiction magazine.

Incidentally, it’s hard not to sense a certain sameness in

tone from many of these pieces. Here are three excerpts:

Lizane was squatting, sitting on her heels, chewing on a

ration bar. She didn’t look surprised to see him and mutely offered him a cup

of the black stuff she poured from the coffee pot.

She was jealous that he’d be part of the second wave – the

first wave had already done the hard work of establishing the colonies, but the

floating cities would be nearly empty, an abundance of unclaimed living space.

She didn’t trust that. She felt a little bad, but people

didn’t just go from being mean to being nice.

With the exception of the final piece (see below), every

story in this issue is a linear narrative told in third person, past tense,

with a relaxed, conversational tone that does not avoid contractions. There’s

nothing wrong with this mode of telling as a stylistic choice, but when almost

every story is dictated in virtually the same register, it’s hard not to feel a

certain monotony creeping in, never mind a sense that possibilities are being

left unexplored. All the writers I admire will work in this mode when it suits

them, but it’s just one of a variety of approaches they can use, each of which

is ready to be deployed when the needs of the story dictate a particular

approach. Of course I’m judging these authors on the basis of a single data

point each, and that’s entirely unfair. But I’ll keeping an eye out for this

sameness of approach as I move through the later issues.

Finally, we come to the longest piece in the issue, a

novella by Allen M Steele entitled “The Long Wait”. Although it can’t be said

to break any particularly new ground, it does what it does very competently.

Unlike the other stories in the issue, it’s a first-person narration told from

the standpoint of an elderly figure looking back over key episodes in their

life. Ostensibly about a privately financed robotic interstellar expedition, the

actual focus of the story is on the family left behind at the Juniper Hill

observatory on Earth to listen for the laser transmissions sent back by the

spacecraft, and how the technology used to launch the probe turns out to have

an unexpected and fortuitous secondary application. The interesting, effective

stuff here is all to do with the inter-familial relationships, rather than the

robotic expedition itself, and Steele doesn’t really put a foot wrong in the

character dynamics, all of which feel plausible and earned within the scope of

the story, which spans many decades. That said, nothing really startling

happens, certainly nothing as weird as the Rucker/Laidlaw piece, and there’s

little here that couldn’t have been published thirty or even forty years ago.

The sense of datedness isn’t helped by the almost exclusively North American

outlook – it’s an American family behind the expedition, the action all takes

place in New England, there’s stuff about DARPA and NSF funding, familiar

American universities and so on, even though most of the action takes place in

the twenty second century. When a killer asteroid shows up, the mining ship

sent to deflect it is named after the Comstock lode, rather than – say – any of

the other places on Earth where they mine stuff. I like my SF to feel a bit

more global and forward-looking than this, but I suppose this all counts as

premise-quibbling so I’ll say no more. It’s unquestionably a piece of solid,

nicely constructed science fiction, even if it won’t leave your world shaken to

its foundations. “Solid” sounds like a minor putdown but I don’t mean it in

that sense; it takes care and craftsmanship to make something solid and Steele

is excellent at what he does.

So there we are – the January issue of Asimovs. There’s nothing

here that left me blown away, but equally there’s nothing offensively bad,

either. And whether or not you regard this as a good thing, each story here is

unambiguously science fiction.